Share via:

Wyeth, N.C. – American Illustrator 1882-1945

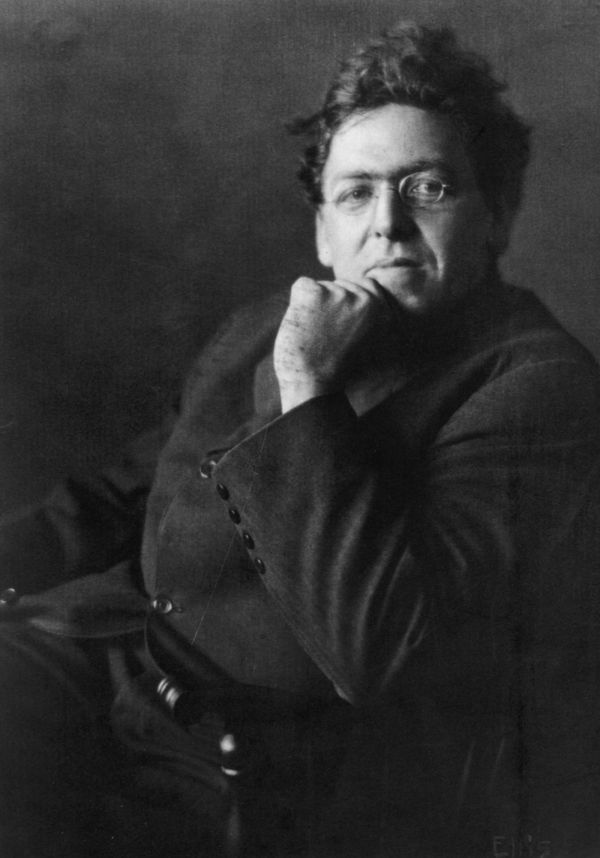

WYETH, N. C. AMERICAN ILLUSTRATOR, 1882-1945. Howard Pyle’s most famous pupil and closest follower, Newell Conyers Wyeth (known professionally by his initials) had an artistic personality quite distinct, in style and substance, from the Master’s.

Raised on a Massachusetts farm staked out by the N.C. Wyeths in 1730, he was a vigorous outdoorsman and a keen observer of nature’s contours and shadings. His letters, otherwise banal, come alive in reference to “mellow, beseeching hills,” to a large blue-black butterfly “lazying his way through the soft air.” The boy who drew horses and other real-life things became, at an art teacher’s suggestion, a student of illustration.

But the training, with its emphasis on cleverness and stunts, rankled; and when word reached Wyeth of Howard Pyle‘s new school in the Brandywine Valley, he was an eager, anxious applicant. The ensuing interview was the pivotal event of Wyeth’s life: though he sometimes criticized Pyle in later years and rued concentrating on illustration, Pyle remained the fountainhead of his aspirations, the impetus to “the unattainable in art.”

Everything about the Pyle studio-school, then at full throttle (see Brandywine School), agreed with Wyeth: the summers at Chadds Ford on the Brandywine; the student camaraderie; the intense effort and inspired teaching; the manifest results. Spurred on by the advanced students’ magazine work, Wyeth painted an oil in the flamboyant Wild West manner—a wild bronco, pitching and twisting to unseat his rider—and submitted it to the Saturday Evening Post; on February 21, 1903, Wyeth’s first professional effort was the Post’s cover illustration, heralding a story by Western writer Emerson Hough, and the young artist, at twenty, was on his way.

The direction was plain. Further Western assignments led to a sketchbook-and-saddle trip through the Southwest, jointly sponsored by the Post and another Wyeth patron, Scribner’s Magazine. Officially a student no longer, Wyeth stayed on at Wilmington, joining other professionals in the Pyle orbit. One slight adjustment remained. Wyeth’s heart was in the gentle, historic Brandywine countryside, so like and unlike his beloved New England, and once married he settled permanently in Chadds Ford.

Through the World War I years Western illustration and magazine illustration flourished—boosted by full-color photographic reproduction—and Wyeth was swamped with assignments. By nature he was a painter of broadly rendered, richly colored and textured oils, not a linear artist like Pyle.

With the advent of the four-color half-tone process, Old Master paintings, reduced to the size of a printed page, came into wide circulation; Wyeth, in turn, made illustrations, on large canvases, that were indistinguishable from full-blown paintings. His compositions not only crackled with action (his mother once begged him for quieter scenes), they made dramatic use of isolated figures, of light and shade, of odd, arresting angles. They had ambiguous depths. Pyle, who mastered every step in the transition from wood-engraved reproduction to half-tone to full color, had also produced some memorable illustrations in oil; N.C. Wyeth, however, was to the medium born.

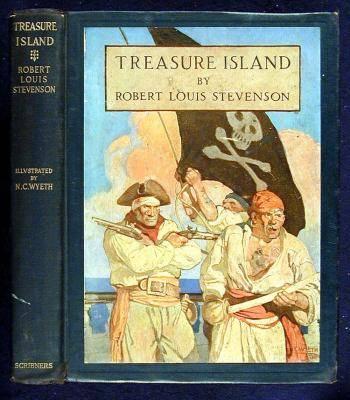

Full-color reproduction had an allure, as well, for publishers of children’s books. The House of Scribner capitalized on its potential by launching a new series of elaborate reprint editions, Scribner Illustrated Classics. Wyeth’s first contribution to the series was Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1911). Printed on coated stock and tipped-in, Wyeth’s fourteen illustrations form a gallery of powerful images, from the explosive action of Billy Bones taking “one last tremendous cut” at the fleeing Black Dog to the doom-laden menace of Blind Pew, “tapping up and down the road in a frenzy.”

Treasure Island was “a phenomenal success,” as Wyeth wrote his mother, and a landmark in children’s book publishing. Scribner’s quickly commissioned Wyeth to illustrate Stevenson’s Kidnapped (1913), putting the Illustrated Classics on a sure course, and other publishers weighed in with similar series, some of them virtually identical in appearance to the Scribner model. This stream of publication is hardly conceivable without Wyeth’s affinity for romantic adventure. For the Scribner series he illustrated fourteen other titles, including The Boy’s King Arthur (1917) and the two most popular Leatherstocking Tales of James Fenimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans (1919) and The Deerslayer (1924), as well as two additional Stevenson titles, The Black Arrow (1916) and David Balfour (1924).

For Harper he illustrated Mark Twain’s Mysterious Stranger (1916); for McKay, Robin Hood (1917) and Rip Van Winkle (1921); for Cosmopolitan, Arthur Conan Doyle‘s White Company (1922), Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1920), and Legends of Charlemagne (1924); for Houghton Mifflin, two dubious choices, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Courtship of Miles Standish (1920) and Homer’s Odyssey (1929).

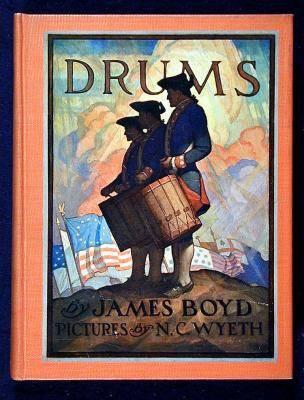

Sometimes Wyeth’s contribution was crucial. Published for adults in 1925, James Boyd’s Revolutionary War novel Drums became a children’s book in the Scribner series with the addition—the added attraction—of illustrations by Wyeth, and Marjorie Kinna Rawlings’s 1938 Pulitzer Prize winner, The Yearling, achieved instant children’s-classic status the following year in the same fashion. Successful as interpretations or not, Wyeth’s illustrations lent a glamour to Classics that lured even indifferent readers and kept some of the titles in print for generations. Recently the best of the Scribner series, beginning with Treasure Island, have been reprinted in facsimiles of the first editions.

By the 1920s Wyeth had largely ceased doing magazine illustration, switching for supplementary income—he was very well paid for his book work—to advertising design, calendar illustration, and other commercial art. color prints of his famous illustrations, displayed in parlors and classrooms, provided still further exposure Indy income. Most gratifying to him were mural commissions, and in the 1930s he also fulfilled his yearning to paint easel pictures. His son Andrew, also a painter and a partial influence on his father, and others of the talented Wyeth brood were already renewing the Brandywine tradition.

Barbara Bader

References:

Silvey, Anita – Children’s Book and Their Creators, Houghton Mifflin, 1996.

- List of Books Illustrated by N.C. Wyeth

- Gallery of N.C. Wyeth Illustrations