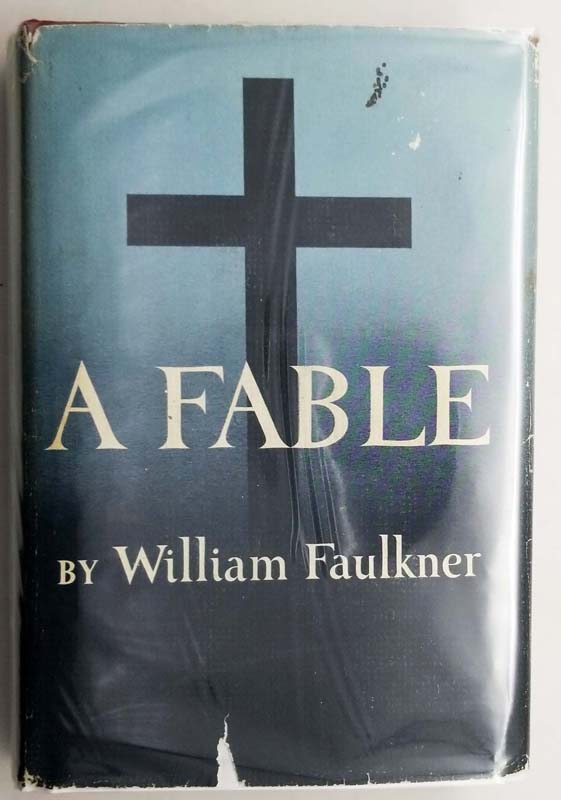

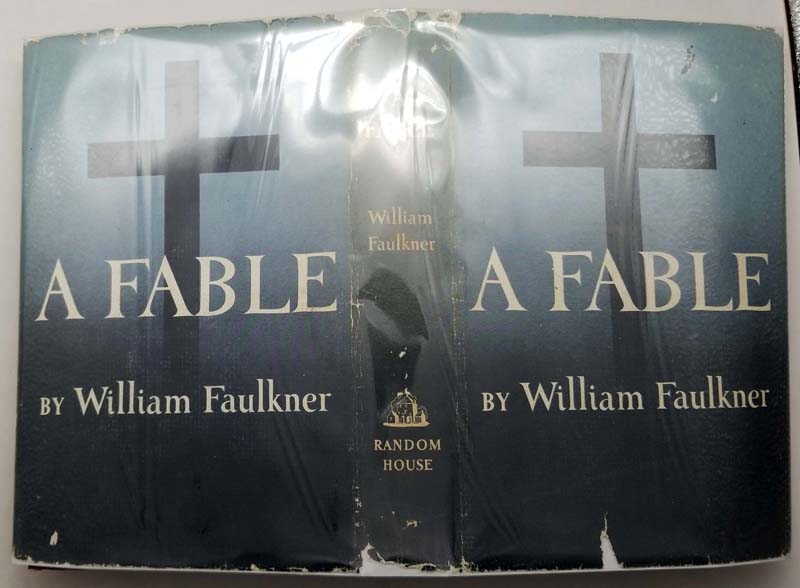

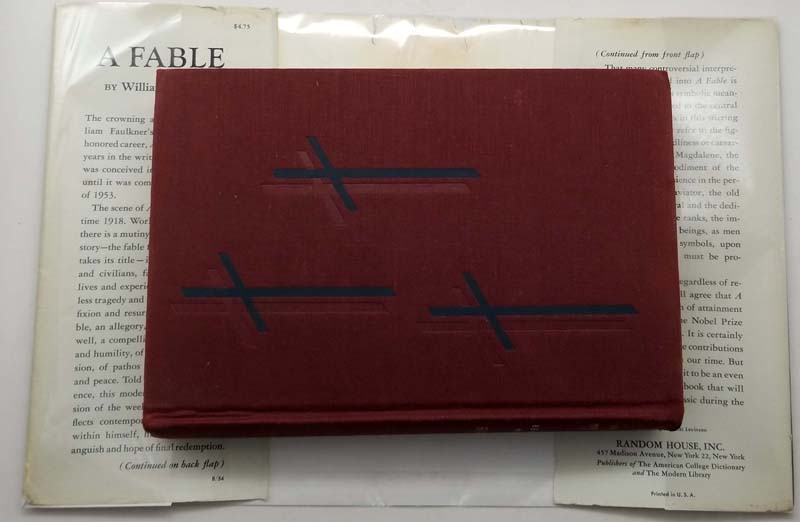

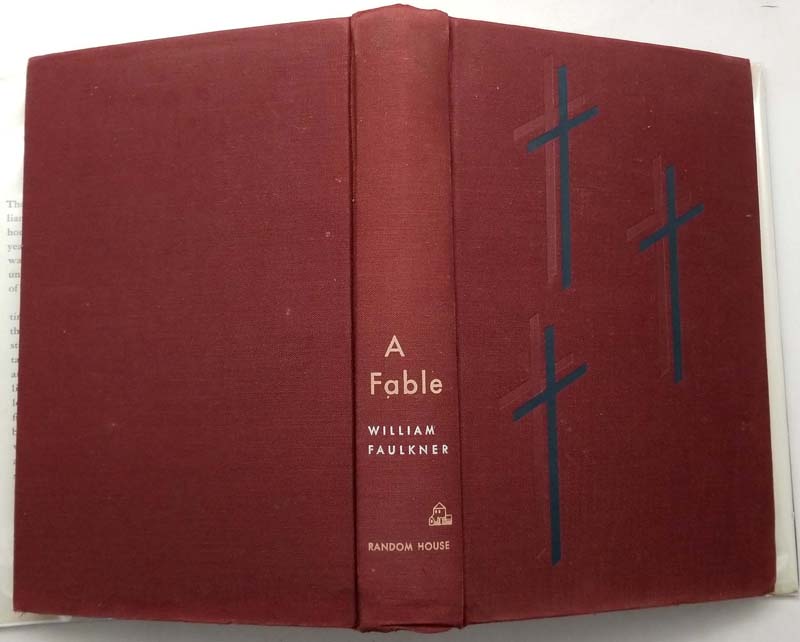

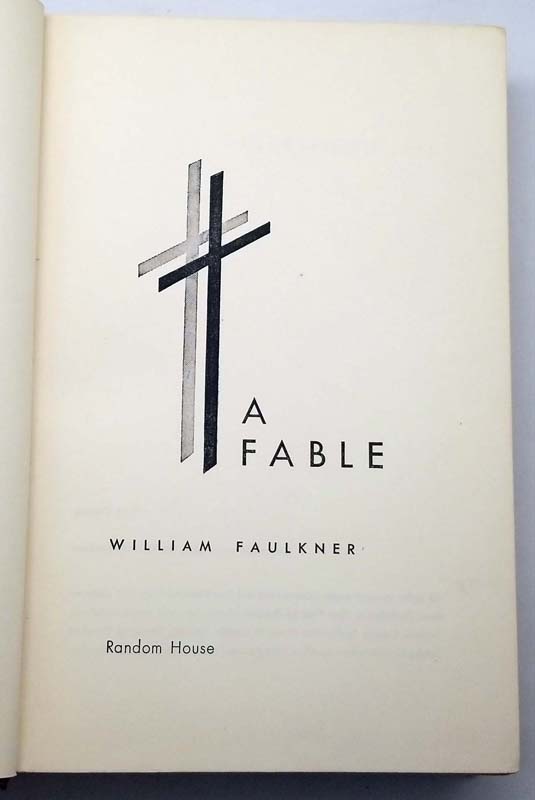

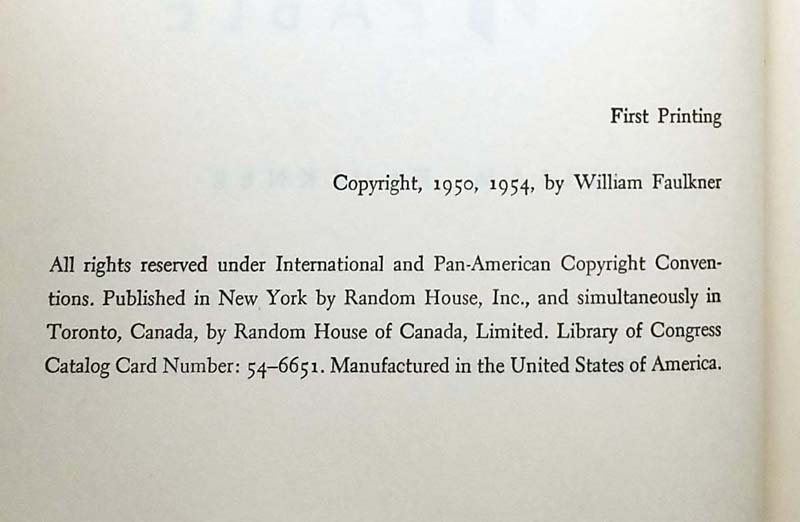

William Faulkner’s A Fable, a radical departure from his Yoknapatawpha saga, is an audacious reimagining of the Christ story set in the trenches of World War I. Winner of both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, the novel unfolds over seven days in 1918 France, where an unnamed Corporal—a quiet, enigmatic figure—orchestrates a miraculous mutiny that brings the war to a temporary standstill. His act of defiance echoes Christ’s rebellion against earthly powers, with the Allied high command (led by the anguished Marshal, a Pontius Pilate figure) forced to confront both the Corporal’s movement and their own complicity in the machinery of war.

Faulkner’s narrative sprawls across perspectives: the Runner, a jaded British officer whose cynicism cracks under the Corporal’s influence; Levine, a Jewish pilot grappling with faith; and a host of soldiers, prostitutes, and generals who embody the novel’s central question—whether one man’s sacrifice can disrupt the endless cycle of violence. The prose is characteristically dense, weaving biblical cadences with modernist fragmentation and sudden bursts of visceral battle imagery.

Though criticized upon release for its convoluted structure, A Fable remains a towering, if flawed, meditation on the paradox of war: its capacity to reveal both the worst of human nature and fleeting glimpses of grace.

“A passion play where the cross is a rifle, the resurrection a rumor, and the only gospel written in mud and mutiny.”

Faulkner considered this his magnum opus, laboring over it for nine years. Today, it stands as his most polarizing work—hailed as visionary by some, dismissed as pretentious by others.