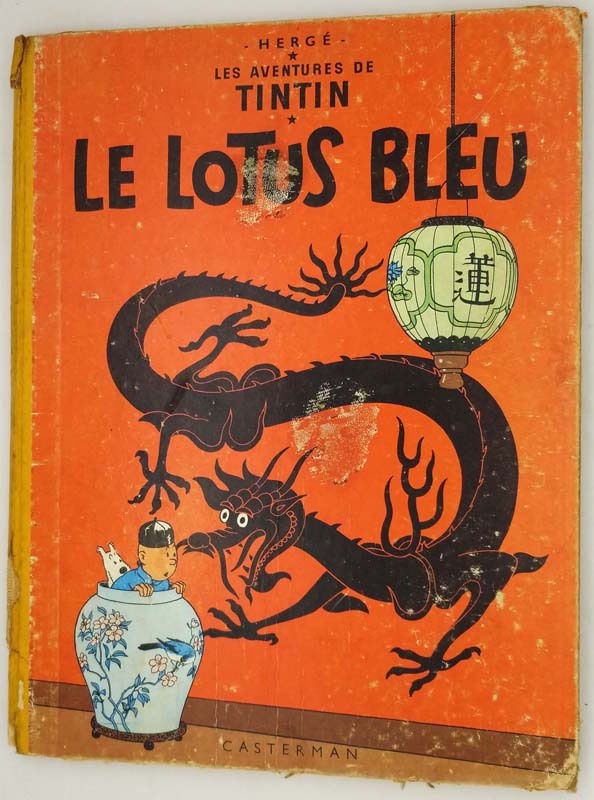

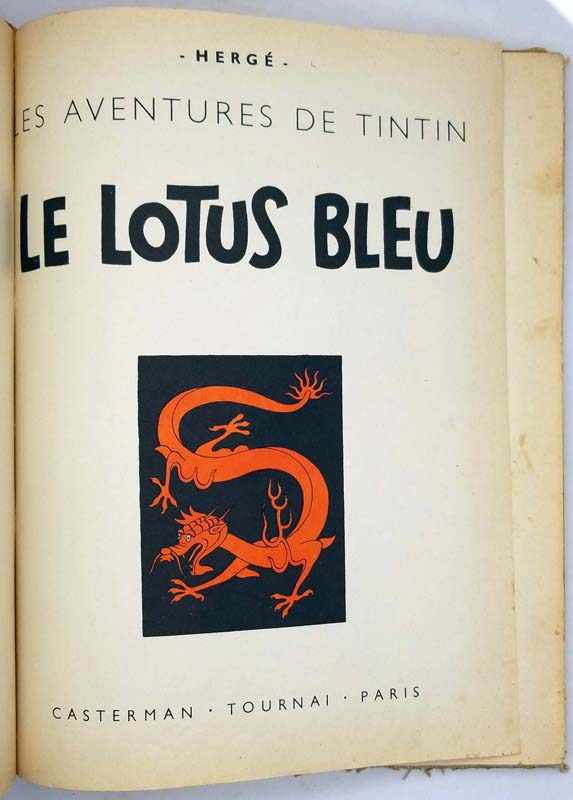

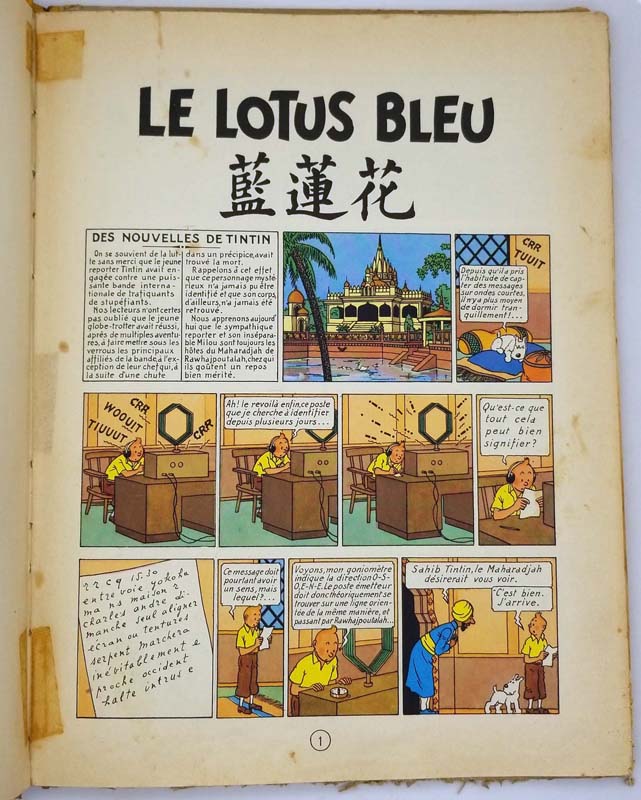

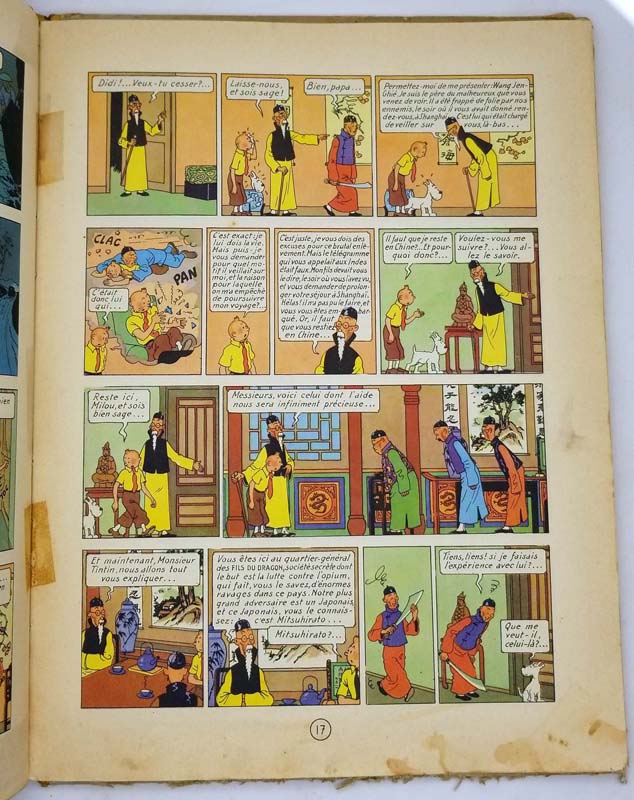

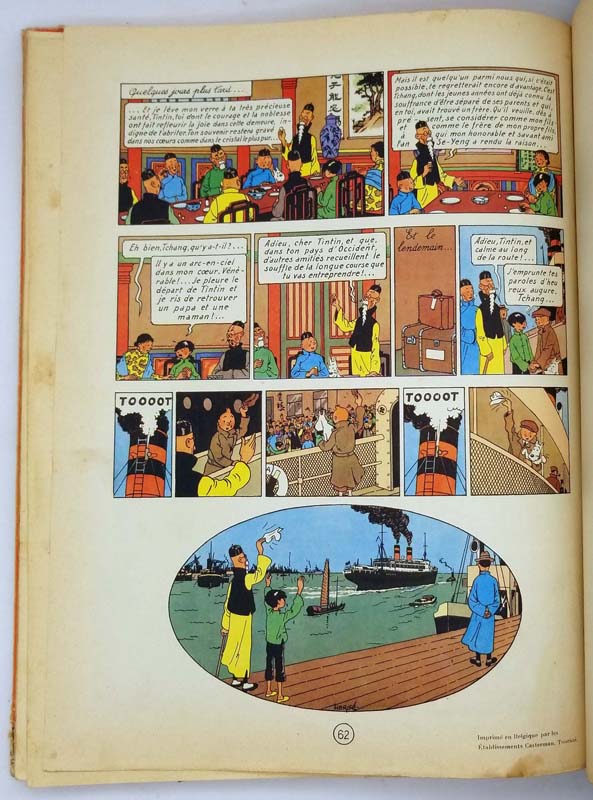

Le Lotus Bleu (1936) by Hergé is the fifth Tintin adventure and a landmark in the series, marking Hergé’s shift toward meticulous research and political engagement. Set in 1930s China during the Japanese invasion, the story follows Tintin as he uncovers a sinister opium-smuggling ring orchestrated by the villainous Mitsuhirato, while befriending the young Chinese boy Tchang (based on Hergé’s real-life friend Zhang Chongren).

The album is celebrated for its anti-imperialist stance and authentic cultural details—Hergé consulted Zhang to avoid caricature, a rarity in European comics of the era. From the haunting depiction of the Lotus Blue opium den to the climactic flood sequence, the story balances thriller pacing with humanist depth.

A turning point in Hergé’s career, Le Lotus Bleu elevated Tintin from mere adventure to art with a conscience.

![A.A. Milne - When We Were Very Young 1924. First edition [1]](https://www.nocloo.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/aam-young1-300x400.jpg)