Charles Perrault – French author, 1628-1703

French author, 162S-1703. The fairy tales written by the French aristocrat Charles Perrault have become such a part of our cultural lexicon that to consider him the “author’’ of such tales as “The Sleeping Beauty,” “Little Red Riding-Hood,” or “Cinderella” would seem almost on a par with naming the “author” of the Old Testament.

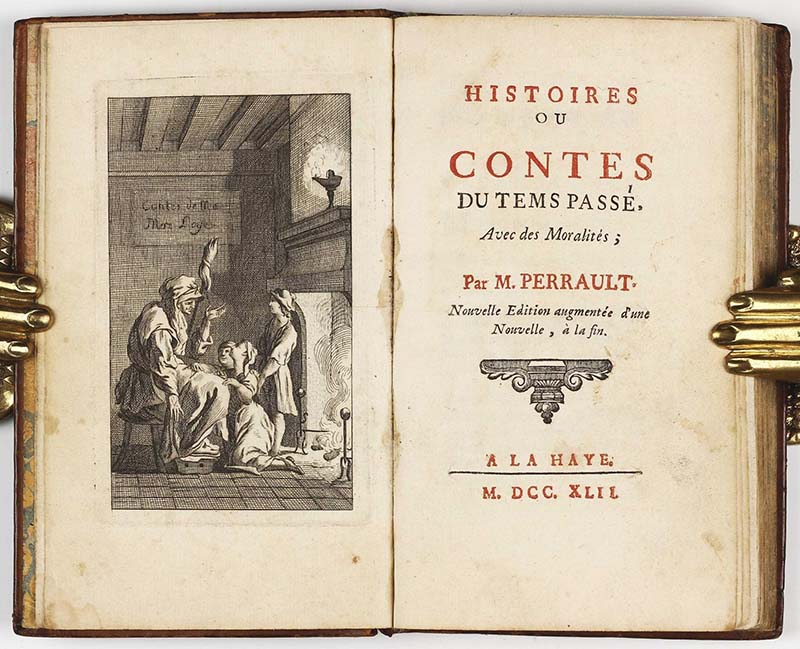

The tales, first published in 1697, are by now an integral part of our collective childhood. Nearly every adult brought up in Western Europe and the United States has heard of one or more of the eight tales; they are, in addition to the three above, “Tom Thumb” (or “Hop O’ My Thumb”), “Bluebeard,” “Puss in Boots,” “The Fairies” (or “Diamonds and Toads”), and “Ricky of the Tuft ”

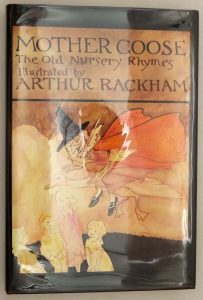

Certainly, Perrault did not make up out of whole cloth the tales that bear his name. Prior to writing down the tales in Histoires et contes du temps passé, avec des Moralités, he had heard them from nurses, parents, and other storytellers or had read versions of the tales himself, perhaps in such works as the Italian Renaissance Pentamerone by Giambattista Basile. The book came to be known as Les Contes de ma mère l’Oye, in recognition of its sources in the traditional tales associated with Mother Goose, a personification of a village storyteller.

The literary structure of the tales—the repetition, for instance, in “Little Red Riding-Hood” (“My, what big eyes you have, Grandmother!”) or the gifts bestowed by the fairies on Sleeping Beauty, accomplishments prized by members of the court of Louis XIV—are all Perrault’s own invention. It is in these embellishments that Perrault made the leap from collecting folklore to writing what has been termed the first “true literature for children.”

Prior to his collection of elegant fairy tales, most books written for children were intended solely to instruct, in keeping with the prevailing attitude that the primary value of children was as the adults they would become, The glorification of childhood for itself and the celebration of children for their innocence and proximity to nature and to God were ideas not fully realized until the Victorian era, a good hundred or so years away. Perrault’s voice was a unique and prophetic one in children’s literature.

Surely he sought to inculcate his young audience with moral character; thus, his stories always see evil punished and virtue rewarded, and each tale is completed by amoral in verse. “Bluebeard,” one of the best known, emphasizes the danger to young girls of succumbing to the blandishments of men. But any reader of the stories can see that Perrault’s primary goal was to entertain.

For example, the moral tacked on to “Puss in Boots”—that native cunning is better than inherited wealth—is completely irrelevant to the rollicking trickster humor of the tale. Perrault did write one tale, “The Princess,” that carried heavy moral weight, but it is rarely retold. The true value of Perrault’s contribution was not his moral instruction but his literary vision.

S.G.K

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.