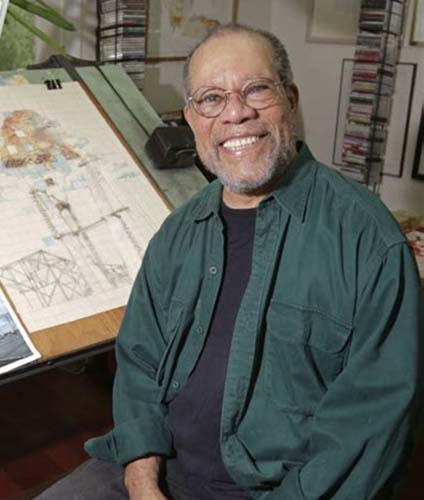

Jerry Pinkney – American Illustrator and writer of children’s books 1939-

Jerry Pinkney, American illustrator, b. 1939. Born in Philadelphia, Jerry Pinkney drew constantly and was recognized as a talented child in school. His parents encouraged him to pursue his talent. As a boy of about twelve, he sold newspapers at a stand, and because he was drawing between sales, he was noticed by a cartoonist, John Lin- ey, who showed him some of the tools of his trade and became one of several mentors. The high school Pinkney attended had a commercial art program, and one of his teachers had a sign-painting business, so Pinkney was able to spend some after-school time gaining experience in several artistic skills. He won a scholarship to the Philadelphia Museum College of Art, where he studied for a number of years and where his technique was at odds with the abstract expressionism his teachers admired. He states that the artists who influenced him were Thomas Eakins, Charles White, Arthur Rackham, and Alan E. Cober.

A few years later, a designer led him to a job at a greeting-card company, where he pursued his interest in the use of typography with illustration. He then became an illustrator-designer for a design studio and illustrated his first book, The Adventures of Spider: A West African Folk Tale, which was published in 1964. Jerry Pinkney later described the sensation of opening that book for the first time and knowing then that creating books was what he wanted to do. In an extensive biographical article in The Horn Book, Pinkney has extolled the marriage of art and design, emphasizing that text and art should work together on a page. He says, “The book represents the ultimate in graphics.” The pacing of narrative, the design, the drawing, and the typography are crucial elements.

He continued to illustrate a succession of folktales. When he illustrated Kasho and the Twin Flutes (1973), however, he states that he began to “deal with getting some kind of emotion and more action in my figures instead of the people just being part of the composition.” He began to take photographs of models reacting to one another, in order to record the movement between them. He illustrated Mildred Taylor’s 1975 novel, Song of the Trees, the first in her well-known books about the Logan family, using his own family as models. As he built up a body of work that included many African and African American characters, he realized that he “had something to contribute, especially in portraying black people.” His realistic drawings of Cassie Logan and her family are synonymous with segregation for a generation of young readers.

Jerry Pinkney in his own words …

I grew up in a small house in Philadelphia. One of six children, with two older brothers and one older sister, 1 was the middle child. I started drawing as far back as I can remember, at the age of four or five. My brothers drew, and in a way I was mimicking them. I found I enjoyed the act of putting marks on paper. It also gave me a way of creating my own space and quiet time, a way of expressing myself.

I attended an all-black elementary school. Because of the difficulty African American teachers had finding employment, Hill Elementary School attracted the best. I left there prepared and with a sense of who I was.

In first grade I had the opportunity to draw a large picture of a fire engine on the blackboard. When the drawing was finished, I was complimented and encouraged to draw more. The attention felt good, and I wanted more. I was not a terrific reader or an adept speller in my growing-up years. Drawing helped me feel good about myself.

My mother and father both supported me. My mother had a sixth sense about me and encouraged me to pursue my dreams. My dad was apprehensive about my pursuing art, but he was responsible for finding and enrolling me in after-school art classes.

There were mentors throughout my life. At age twelve I had a newspaper stand and would take a drawing pad to work with me, sketching people as they waited for a bus or trolley. John Liney, at that time the cartoonist of “Little Henry,” would pass the newsstand on his way to his studio. He took notice of my drawing and invited me to visit his studio. There I learned about the possibility of making a living creating pictures. What an eye opener! I visited John’s studio often, and we became friends.

Roosevelt Junior High was an integrated school. I had many friends, white and black, at a time when there was little social mixing in school. At Roosevelt the spark for my curiosity about people was lit. This interest and fascination with people of different cultures appears throughout my work.

My formal art training started at Dobbins Vocational High School, where I majored in commercial art. There I met my first African American artist and educator, Sam Brown. Upon graduation I received a scholarship to the Philadelphia Museum College of Art, where I studied in advertising and design.

When I left school, I freelanced in typography and hand lettering. In i960 I had the opportunity to go to Boston and work for Rust Craft Greeting Cards. Along with my wife, Gloria Jean, and our first child, I moved to Boston. Boston provided good opportunities for me, because it was a publishing center. I was there at a time during which publishers were reconstructing their ideas about textbooks. The late 1960s and early 1970s brought about an awareness of the need for African American writers. Publishers sought out African American illustrators for this work. And there I was.

From the very beginning of my career in illustrating books, research has been important. I do as much as possible on a given subject, whether it has anything directly to do with the project or not, so that I live the experience and have a vision of the people and the places. To capture a sense of realism for characters in my work, I use models that resemble as much as possible the people I want to portray. Gloria has been assisting me in finding the models. We keep a closet full of old clothes to dress up the models, and I have people act out the story. I take photos to aid me in better understanding body language and facial expressions.Once I have that photo as reference, I have freedom, because the more you know the more you can be inventive.

In illustrating stories about animals, as with people, research is important. I keep a large reference file and have over a hundred books on nature and animals. The first step in envisioning a creature is for me to pretend to be that particular animal. I think about its size and the sounds it makes, how it moves, where it lives. When the stories call for anthropomorphic animals, I’ve used Polaroid photographs of myself posing as the animal characters.

Recently, I have been concentrating on doing books about people of color. As an African American artist doing black subject matter, I try to portray a sense of celebration, of self-respect and resilience, and also a sense of dignity.

It still amazes me how much the projects I have illustrated have given back to me—the personal as well as the artistic satisfaction. They have given me the opportunity to use my imagination to draw, to paint, and to travel through the voices of the characters in the stories—and above all else, to touch children.

His illustrations for The Patchwork Quilt (1985), a warm story of the members of an extended family who construct a quilt together, won a 1986 Coretta Scott King Award. He won the award again the next year for Haifa Moon and One Whole Star (1986). In 1987 he illustrated The Tales of Uncle Remus, in which Julius Lester retold the Joel Chandler Harris collection of folktales. Two more volumes of the highly acclaimed stories were published with his illustrations. Mirandy and Brother Wind (1988), a 1989 Caldecott Honor Book and a winner of the 1989 Coretta Scott King Award for illustration, celebrates African American culture in a picture book based on a cakewalk dance contest in the 1900s.

Jerry Pinkney says he likes to put a lot of information in his artwork. For this reason, research is important to him. In addition to his books for children, he has illustrated many limited-edition books of classic literature and has created commemorative stamps for the U.S. Postal Service. He has had many one-man shows arid has been a speaker at colleges, universities, and museums. He is also associate professor of art at the University of Delaware and enjoys encouraging young artists.

S.H.H.

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.