Chris Van Allsburg – American illustrator and author, b. 1949.

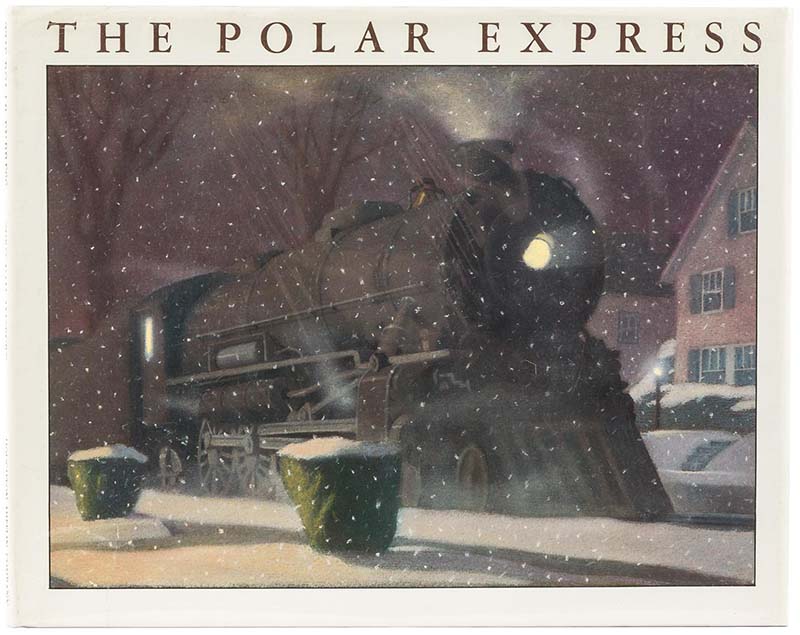

American illustrator and author, b. 1949. The publication and subsequent success of Chris Van Allsburgs The Polar Express (1985) clearly established the illustrator-author as one of the premier creators of picture books in twentieth-century children’s literature. The Polar Express, immediately taken to heart by children and adults alike, was a phenomenon in children’s publishing. It won the Caldecott Medal for illustration, appeared on the New York Times best seller list, sold more than a million copies in its first five years of publication, and achieved the status of a contemporary classic.

The story chronicles the adventures of a boy who boards the Polar Express, travels to the North Pole, meets Santa Claus, and is given a silver bell. Its sound can be heard only by those who believe in the impossible—that is, in Santa Claus. Rich pastel illustrations, in blues and purples, are accompanied by a narrative that achieves an exceptional sense of story. The story appeals because Van Allsburg touches a universal chord —faith. The simple truth of the story is perceptively conveyed through a felicitous blend of pictures and narrative; the combination radiates with childlike wonder while reverberating with mysterious intensity.

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Van Allsburg received his B.EA. from the University of Michigan. He attended graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design and received his M.EA. in sculpture. In 1977, Van Allsburg’s sculptures, described as “fastidiously crafted, surreal, enigmatic and whimsical,” were exhibited in New York galleries. Originally, he began drawing as a casual diversion from sculpting, and his early black-‘ and-white drawings contained elements of sculpture— heavy, solid forms, which appear to be built with even, controlled lines and architectural perspectives.

While The Polar Express unquestionably ranks as Van Allsburgs most popular book, it is only a part of his contribution to children’s books. His first book, The Garden of Abdul Gasazi (1979), met with a variety of critical responses. The striking, pointillistic graphite I drawings were hailed as “intriguing and refreshing.”The story, about a young boy pursuing a dog into the topiary gardens of the magician Gasazi, was labeled ominous | and disquieting by some. The book won the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award for illustration; it was considered an auspicious beginning.

Chis Van Allsburgs in his own words …

Over the years that have passed since my first book was published, a question I’ve been asked often is “Where do your ideas come from?” I’ve given a variety of answers to this question, such as “I steal them from the neighborhood kids” or “They are beamed to me from outer space”.

It’s not really my intention to be rude or smartalecky. The fact is, I don’t know where my ideas come from. Each story I’ve written starts out as a vague idea that seems to be going nowhere, then suddenly materializes as a completed concept. It almost seems ftp a discovery, as if the story were always there. The few elements I start out with are actually dues. If I figure out what they mean, I can discover the story that’s waiting.

When I began thinking about what became The Polar Express, I had a single image in mind: a young boy sees a train standing still in front of his house one night The boy and I took a few different trips on the train, but we did not, in a figurative sense, go anywhere. Then I headed north, and I got the feeling I that this time I’d picked the right direction, because the train kept rolling all the way to the North Pole. At that point the story seemed literally to present itself.

I Who lives at the North Pole? Santa. When would the I perfect time for a visit be? Christmas Eve. What happens on Christmas Eve at the North Pole? Undoubtedly, a ceremony of some kind, a ceremony requiring a child, delivered by a train that would have to be I I named the Polar Express.

These stray elements are, of course, merely events. A good story uses the description of events to reveal some kind of moral or psychological premise. I am not aware, as I develop a story, what the premise is.

When I started the book, I thought I was writing I about a train trip, but the story was actually about faith and the desire to believe in something. Creating books is an intriguing process. I know if I’d set out with the goal of writing a book about faith, I’d still be holding a pencil over a blank sheet of paper.

Santa Claus is our culture’s only mythic figure truly believed in by a large percentage of the population. Most of the true believers are under and that’s a pity. The rationality we all embrace as adults makes believing in the fantastic impossible. Lucky are the children who know there is a jolly fat man in a red suit who pilots a flying sleigh. We should envy them. And we should envy the people who are so certain Martians will land in their back yard that they keep a loaded Polaroid camera by the back door. The inclination to believe in the fantastic may strike some as a failure in logic, but it’s really a gift. A world that might have Bigfoot and the Loch Ness monster is clearly superior to one that does not.

The application of logical or analytical thought may be the enemy of belief in the fantastic, but it is not, for me, a liability in its illustration. When I conceived of the North Pole in the book, it was logic that insisted it be a vast collection of factories. I don’t see this as a whim of mine or even as an act of imagination. How could it look any other way, given the volume of toys produced there every year?

I do not find that illustrating a story has the same quality of discovery as writing it. As I consider a story, I see it quite clearly. Illustrating is simply a matter of drawing something I’ve already’ experienced in my mind s eye. Because I see the story unfold as if it were on film, the challenge is deciding precisely which moment should be illustrated and from what point of view.

A fantasy of mine is a miraculous machine, a machine that could be hooked up to my brain and instantly produce finished art from the images in my mind. Conceiving something is only part of the creative process. Giving life to the conception is the ocher half. The struggle to master a medium, whether it’s words, notes, paint, or marble, is the heroic part of making art.

Van Allsburg has stated that stories begin as fragments of pictures in his mind. “Creating the story comes out of posing questions to myself. I call it the ‘what if and ‘what then’ approach. What if two bored children discover a board game? What then … ?” That was the beginning of Jumanji (1981). As the protagonists, Judy and Peter, play the game, their house is transformed into a jungle—complete with a hungry lion, marauding monkeys, a menacing python, and an erupting volcano. The children know they must finish the game, and in a chaotic final moment all is set right when one player reaches the end. Readers are spellbound by this cautionary adventure and delight in the final page when they witness the game being discovered by two more curious children. Masterly use of light and shadow and exaggerated changes of perspective create a bizarre and mythical world that leaves one wondering whether the adventure was real or imagined.

In The Wreck of the Zephyr (1983), a story about the disasters wrought by youthful pride, the artist leaves the dramatic tonal range of grays and black and white characteristic of previous books—and bursts into color. Using pastels, he creates vibrant, luminous landscapes. The sharp delineation of figures and objects found in earlier work is more diffused here, imbuing the illustrations with a mysterious light.

This softening of line is carried into The Mysteries of Harris Burdick (1984), where richly shaded charcoal drawings intrigue and tantalize the imagination. The book is composed of fourteen illustrations, labeled with captions, Pictures range from whimsical to frightening, and are linked by unexplained elements or the supernatural. The book’s enigmatic premise and the exquisite drawings, which speak eloquently without text, represent qualities that have become hallmarks of Van Allsburg’s work.

Magic and the supernatural in The Widow’s Broom 1993) are tempered by the practical, kindly nature of widow, who assists a witch and is given her broom. Good versus evil is the theme, but the story bubbles with humor and affection when the protective, magic broom and the widow become fast friends.

Van Allsburg’s artistic style is often described as surrealistic fantasy. Van Allsburg states that “he is intrigued by a setting of a normal, everyday reality, where something strange or puzzling happens; he also enjoys creating impossible worlds.” So, it is not surprising that visual illusions, created by the dramatic use of scale and perspective, are a common thread running through his books.

Also characteristic of Van Allsburg’s illustrations are forms and figures that—to varying degrees— appear sculptured and frozen in time. But the breadth and sophistication in his style also allow for fluid, subtle nuances in human figures and detailed facial expressions, which reflect deeper psychological interpretations of character. Whether executed in black and white or in color, Van Allsburg’s illustrations never fail to fascinate the intellect, pique the senses, and emphasize the power of imagination.

Stephanie Loer

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.

Chris Van Allsburg Books

- The Garden of Abdul Gasazi (1979), a Caldecott runner-up

- Jumanji (1981), a Caldecott Medal winner

- Ben’s Dream (1982)

- The Wreck of the Zephyr (1983)

- The Mysteries of Harris Burdick (first ed., 1984)

- The Enchanted World: Ghosts (1984)

- The Polar Express (1985), a Caldecott Medal winner The Enchanted World: Dwarfs (1985)

- The Stranger (1986) The Z Was Zapped (1987)

- Two Bad Ants (1988)

- Just a Dream (1990)

- The Wretched Stone (1991)

- The Widow’s Broom (1992)

- The Sweetest Fig (1993)

- The Mysteries of Harris Burdick (Portfolio ed., 1994) Bad Day at Riverbend (1995)

- A City in Winter (1996), written by Mark Helprin

- Zathura (2002)

- Probuditi! (2006)

- Queen of the Falls (2011)