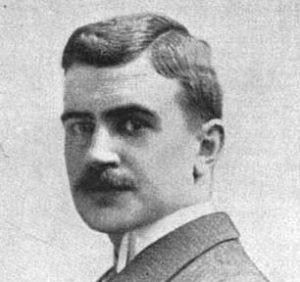

George Cruikshank – British caricaturist and book illustrator (1792-1878)

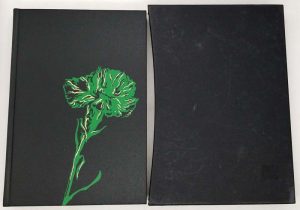

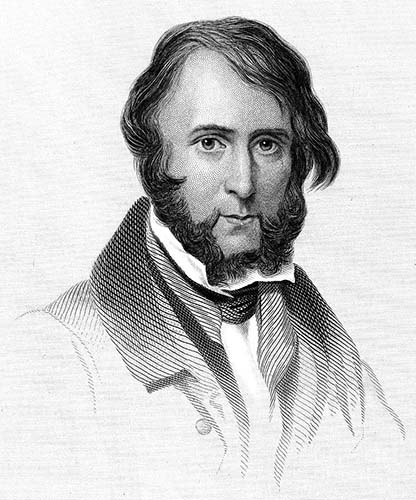

George Cruikshank (1792-1878) was born in London. He had little formal education and no specialized art training beyond serving an apprenticeship to his father, Isaac, a hack engraver whose early death precipitated George’s prolific and varied career. While his satiric wit was in the tradition of the eighteenth-century caricaturists, William Hogarth, James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, it was more whimsical than vulgar. He shared their critically incisive perception of society and politics. Cruikshank’s diverse subject range reflected three generations of English life — the Regency, the Reform era and the Victorian milieu. Generally, he etched his own drawings on copperplates (after 1840 on steel) or designed directly on wood for another engraver.

In 1823 he produced twelve superb etchings for German Popular Stories, the first English selection from Grimm; for a second volume in 1826 he contributed ten more. The critic John Ruskin, introducing a reissue in 1868, extravagantly praised Cruikshank’s art as the rival of Rembrandt’s.

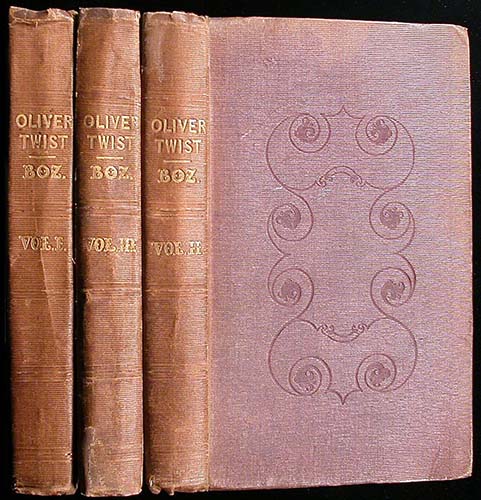

As Charles Dickens’s first illustrator, Cruikshank etched plates for Sketches by Boz (1836) and for the serialized installments of Oliver Twist (1837). Bitter at seeing the bulk of the profit and praise elude him, Cruikshank quarreled chronically with his associates, although many of them generously contributed material to the numerous, short-lived publications which he edited.

In 1847 Cruikshank fanatically espoused the temperance cause. Hop-o’my-Thumb (1853), the first in the Fairy Library series, was a direct outgrowth of this conversion. It was followed by Cinderella and Jack and the Bean-Stalk (both 1854), Puss in Boots (1864) and a collected edition in 1865. Although his illustrations escaped the didactic bias of his text, reflecting the narrative compactness and imaginative vision that characterized his best work, the series proved a dismal commercial failure.

‘Hop-o’my-Thumb’ first appeared as ‘Le Petit Poucet’ in Charles Perrault’s Histoires (1697). The hero is the youngest of a poor family. His parents plan to abandon their seven sons in the woods rather than watch them die of hunger. Little Poucet overhears and drops a trail of white pebbles to lead his brothers safely home. On a second attempt he has only bread-crumbs to scatter which are eaten by birds. The children wander to the house of an ogre whose wife hides them until her husband smells them out. That night, Poucet exchanges the boys’ caps for the crowns of the seven daughters of the ogre who then mistakenly slaughters them. The brothers escape, pursued by the ogre in seven-league boots. Poucet steals the boots and then outwits the ogress of her husband’s money which he presents to his parents.

The fact that the ogre’s brutality is induced by alcohol suggested this tale as a natural framework for Cruikshank’s doctrines. In his adaptation the father is a count, fallen through bad companions from fortune into drunkenness which drives him to the unnatural act of abandoning his children. Cruikshank deleted as ‘objectionable’ the giant’s cutting of his daughters’ throats, Hop’s lying to the giantess and his subsequent stealing. The seven-league boots trip the giant because he is not sober. Hop removes the boots and presents them to the king who restores the family’s position and passes a law abolishing the use of intoxicating liquors.

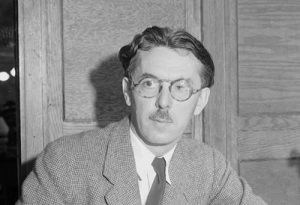

Charles Dickens was moved to good-humoured but strong protest at Cruikshank’s ‘presumption’ in altering traditional tales ‘to suit his own opinions’ and published ‘Frauds on the Fairies’ in the periodical Household Words (1853), praising the pictures but attacking the text.

The artist was incensed at Dickens’s censure and retaliated by publishing ‘A letter from Hop-o’my-Thumb to Charles Dickens, Esq.’ in George Cruikshank’s Magazine. Their twenty-year friendship, often strained, dissolved. Dickens described Cruikshank as ‘a live caricature himself’.

George Cruikshank argued that if, as Dickens stated, fairy tales affected youthful minds, then all vulgarity and deceit should be eliminated. Children should only be presented with pure first impressions, ‘morally useful to them through life’. He viewed drunkenness as the root of poverty, disease and crime. He warned children not to believe in fairies or giants who were only meant to ‘amuse and convey good lessons and advice’.

After this public dispute George Cruikshank’s disillusionment and eccentricity grew and his talent declined. He continued to be denied membership in the Royal Academy and was forced to accept charitable assistance. Cruikshank continued etching until the age of eighty-three and upon his death was buried in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Source: English Illustrated Books for Children, edited by Margaret Crawford Maloney.