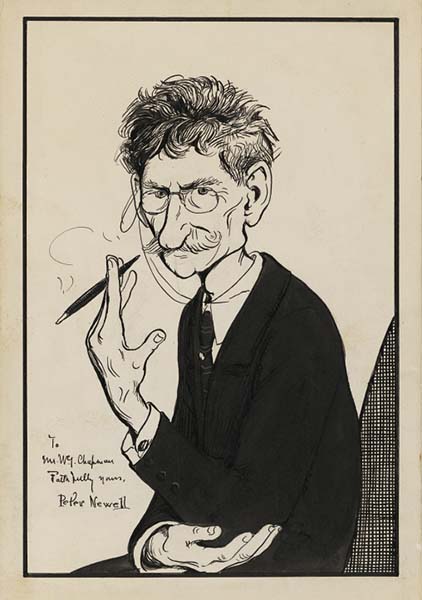

Peter Newell – American humorist and illustrator, 1862- 1924

Peter Newell drew like no one else and created picture books like no others. A humorist famously sober of mien, he was a true original.

Two anecdotes are always told about Newell—stories that, poker-faced, he liked to tell about himself. As a young tyro in a small Illinois town, he sent a humorous drawing to the editor of Harper’s Bazaar with a note asking if it showed talent. “No talent indicated,” came the reply, but a check was enclosed, sales to other magazines took him to New York and a few months’ formal study before he decided to remain unschooled and unassimilated, or, to his way of thinking, himself.

He was, however, a thoroughgoing professional. Capitalizing on the new method of halftone reproduction, he introduced in America the technique of drawing in flat halftone washes developed by the French illustrator Maurice Boutet de Monvel, and, for maximum effect at minimum cost, he planned many of his illustrations to be printed in black-and-white with a single second color each, a practice that later became common.

His plain-as-plain style, with its moon-faced, popeyed, goblinlike figures, looked decidedly spooky to some and like no style at all to many. But as the graphic arts connoisseur Philip Hofer points out, “He used simple means because he liked simple subjects. Probably he chose both because he was thinking of his audience: children, and grown-ups who retain their youth.”

Much of Newell’s work has that dual appeal. His first big success was an illustrated nonsense jingle, “Wild Flowers,” which appeared in Harpers magazine in August 1893. A solicitous schoolmaster bends over a trembling little girl:

"Of what are you afraid, my child? inquired

the kindly teacher.

'Oh, sir! the flowers, they are wild,'

replied the timid creature.”At the same time he illustrated books: nonsense for all and sundry by Guy Wetmore Carryl and Caroline Wells; the absurdist humor of John Kendrick Bangs’s Houseboat on the Styx (1896) and its sequel, The Pursuit of die Houseboat (1897); and, following Lewis Carroll’s death in 1898 and the end of his control, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1901) and Through the Looking Glass (1902).

Peter Newell’s Alice, the most prominent of four new American editions issued between 1899 and 1904, was roundly denounced and just as firmly if less widely defended, with Newell himself taking the lead in favor of fresh interpretations. Today, after a century of Alice in Wonderland makeovers by artists of every bent, Newell’s formalized compositions and histrionic airs look considerably less peculiar and often quite aptly comical.

His third major sphere of activity, the making of picture books, came about by chance, though given his inventiveness, hardly by accident. As the cherished Newell anecdote goes, he spotted one of his offspring looking at a picture book upside down and determined to produce a book that could be turned around. The result was Topsys & Turvys (1893), which is reversible page by page. Thus, “In sandy groves Adolphus swings when Summer zephyrs blow” reverses to become “And slides head foremost down the hill when Winter brings the snow.” Acclaim was immediate, and a second series of Topsys & Turvys appeared the next year.

How The Hole Book (1908) came about we do not know, or need to. Of picture-book inventions, it comes dose to sheer, ungimmicky inspiration; among novelties, it is one of the few with perennial appeal. The fun starts on the cover, as a procession of boys and girls approaches a tantalizing hole straight down into the interior; who, then, can resist the invitation to “open the book and follow the hole.” Inside a boy accidentally shoots off a gun and the bullet makes a flying entrance into scene after peaceful scene, cutting the rope of a backyard swing, shattering a goldfish bowl, sending a high silk hat a-sailing via a hole cut in each page. An instantaneous hit, so to speak.

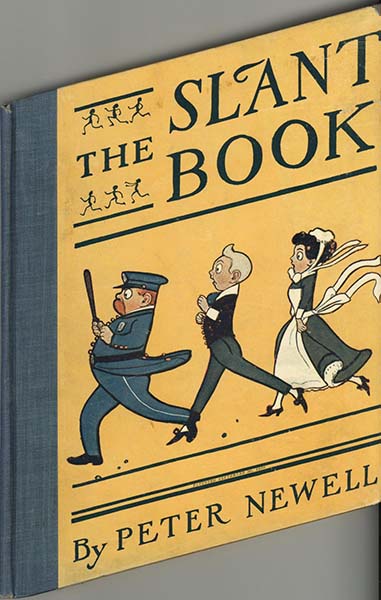

The Hole Book led Peter Newell into other innovations in format. The Slant Book (1910), in the shape of a parallelogram with pictures and verses on the diagonal, has a runaway baby carriage spilling the contents of a pushcart, tumbling a painter from his ladder (with messy results for a passer-by), literally slicing through a watermelon patch—all to the intense delight of the infant passenger. The Rocket Book (1912) repeats the pattern of The Hole Book on the vertical, as a rocket set off by the janitor’s son Fritz in the basement shoots up through die twenty-one stories of the apartment houses causing predictable and unpredictable havoc among the social types en route.. Philip Hofer, a Newell fan, saw in his work admirable, all-American slapstick. American-art historian Edgar Richardson discerned in Peter Newell a forerunner of “the gentle humor of the absurd” later cultivated in The New Yorker. Both, of course, were right.

B.B.

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.