Wanda Gág – American author and illustrator, 1893-1946

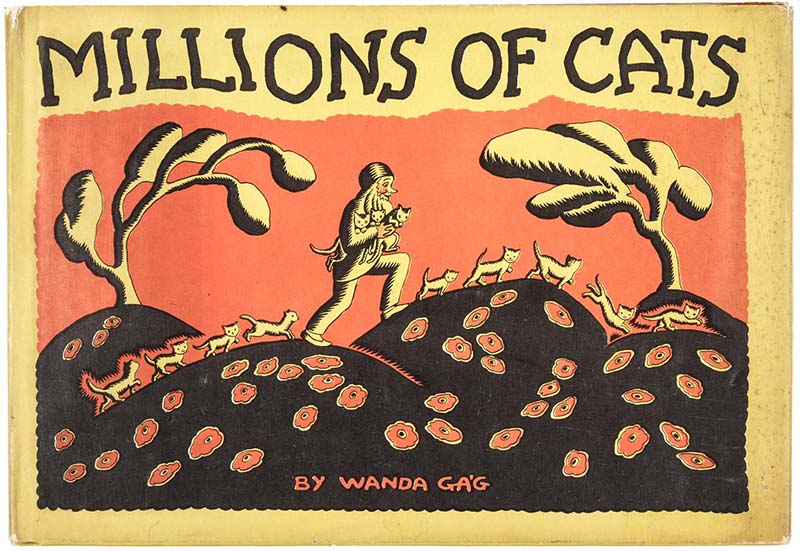

American author and illustrator, 1893—1946. Ernestine Evans, editor for a new publisher, was determined to make children’s books using the best fine-art artists in America. She knew the art of Wanda Gág— Gág’s pictures, she recollects, were “beautiful, and very simple, and full of the wonder of common things.” So Evans made an appointment to meet her at the Weyhe Gallery in New York, where Gag was having a one-woman show. Out of that meeting came the classic favorite: Millions of Cats (1928). Evans says, “When we had in the office the marvelous manuscript of Millions of Cats, I hugged myself, as children all over the country have been doing ever since.”

The simple story, with its roots grounded in folklore, tells of a lonely old man and a lonely old woman who just want a kitten to love. So the old man trudges over hills and valleys until “he came to a hill which was quite covered with cats.” And with this, Gág introduces the silly, lyrical lines that have delighted children for more than sixty years: “Cats here, cats there, Cats and kittens everywhere. Hundreds of cats, Thousands of cats, Millions and billions and trillions of cats.”

Of course, when the old man tries to choose among them, he ends up liking them all, for each one is as pretty as the next. When he brings these hundreds of cats back home, he and the old woman have to choose just one. The cats fight over who is the prettiest, and when they are done, only one very ugly kitten is left. The ending, as the kitten turns into the most beautiful cat in the world through loving care, is shown primarily through Gag’s soft, round illustrations, lively with humor.

The entire book is done in black and-white—“small, sturdy peasant drawings” Gág called them, and the hand-lettered text, done by her brother, is as solid and round as the pictures. The strength of Millions of Cats is that it has its roots in a compelling childhood. Wanda Gág was the eldest of seven children in a German family in New Ulm, Minnesota.

Both her parents were artists; her father, in particular, had talent that was frustrated by the needs of providing for a large family. When he died of tuberculosis his last coherent words were whispered to his fifteen year-old daughter: “Was der Papa nicht than konnt, mub die Wanda halt fertig machen.”—“What your Papa could not do, Wanda will have to finish.” This directive enflamed the girl’s passion for art. She studied, all expenses paid, at the St. Paul Art School, and in 1926 her first major show opened in New York. After this exhibit, Gag focused on printmaking, an art that lent itself to the bookmaking she was one day to do.

The year after Millions of Cats, Gág came out with The Funny Thing (1929), artistically distinguished but with a disappointing story, and two years later Snippy and Snappy (1931), the story of two young mice. She used the same technique for refining the story line in all three books: She told it again and again to all the children she knew until the words sang with rhythm and internal rhyme.

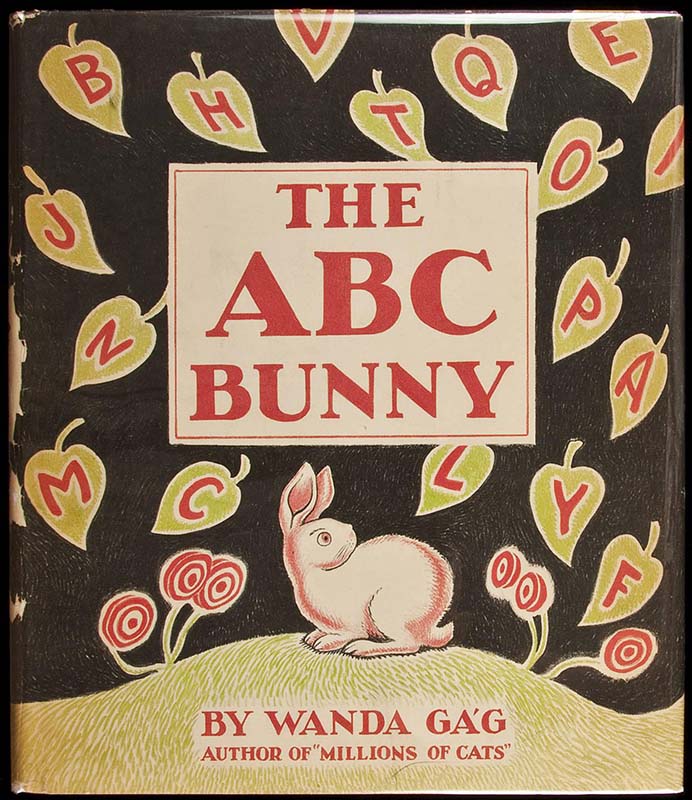

Wanda Gág worked in lithograph for The ABC Bunny (1933)1 a technique of wax crayon on zinc plates that allowed for no mistakes. The medium provided her with a rich gray scale, and she played this off brilliant red capital letters. The book is a simple story of a bunny, set outdoors. The location gave Gág a framework to work out the artistic principles with which she was grappling- Especially On the page “V for View/Valley too,” Gag created the rolling hills with a series of tightly formed contour lanes, similar to Van Gogh’s.

She wrote: “Just now I’m wrangling with hills. One would never guess [they] could be composed of such a disturbing collection of planes. The trouble is each integral part insists on living a perspective life all its own.” Far from the disturbing emotional quality Van Gogh projects, Gág’s drawings fill the page with a sense of safe wonder.

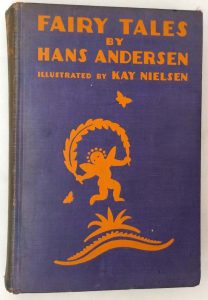

As a children’s book artist, Gág became interested in the old German Marchen, the folk and fairy tales of her childhood. She studied die Grimm stories in the original German and read them in English translation. Often they felt flat, affected, and artificial to her, lacking the lively vigor of a storyteller’s voice. So Gag decided to retranslate the stories, a “free” translation that would be truer to their native spirit. She found most of her childhood favorites among the Grimms’ collection, but one of the funniest was missing. Gág retold from memory the story that became Gone Is Gone; or, The Story of a Man who Wanted to Do Housework (1935).

A few years later she did a similar single-story volume of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1938) to coincide with the release of the first Walt Disney movie, which she and many others felt had trivialized, sterilized, and sentimentalized the potent old story. In her first collection, Tales from Grimm (1936), Gág created a mesmerizing mood by using straightforward Anglo-Saxon words in rounded, repetitive lines: “A fiery dragon came flying along and lay down in the field, coiling himself in and out among the rye-stalks.”

At last, by 1945, Gág felt that her life was in order: Her younger brothers and sisters were all well situated; her career was blooming with awards—she had won two Newbery Honor Awards for Millions of Cats and for ABC Bunny and two Caldecott Medals for Snow White and for Nothing at All (1941), a story about an invisible dog.

She was ready to do her final volume of Grimm tales when she went to visit the doctor. Her husband, Earle Humphreys, hid the news from her: She had lung cancer and had only three months to live. They went to Florida for the warm air, and she continued working on the books from her bed. Defying all predictions, Gág lived another seventeen months, returned to her beloved home All Creation, in the Musconetcong Mountain region of New Jersey, and very nearly completed the final volume of Grimms’ tales. She left clear notes and instructions for her editor, and except for a few unfinished drawings, More Tales from Grimm (1947) was published, in the form she had planned for it, after her death.

The works that Wanda Gág created in the first half of the century are still cherished today, for in her strong, homey pictures and singing text she produced classic books that children will return to time and time again.

J. Alison James

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.

Wanda Gág Books

Writer and illustrator:

- Batiking at Home: a Handbook for Beginners, Coward McCann, 1926

- Millions of Cats, Coward McCann, 1928

- The Funny Thing, Coward McCann, 1929

- Snippy and Snappy, Coward McCann, 1931

- Wanda Gág’s Storybook (includes Millions of Cats, The Funny Thing, Snippy and Snappy), Coward McCann, 1932

- The ABC Bunny, Coward McCann, 1933

- Gone is Gone; or, the Story of a Man Who Wanted to Do Housework, Coward McCann, 1935

- Growing Pains: Diaries and Drawings for the Years 1908-1917, Coward McCann, 1940

- Nothing At All, Coward McCann, 1941

Translator and illustrator:

- Tales from Grimm, Coward McCann, 1936

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Coward McCann, 1938

- Three Gay Tales from Grimm, Coward McCann, 1943

- More Tales from Grimm, Coward McCann, 1947

Illustrator only:

- A Child’s Book of Folk-Lore— Mechanics of Written English, by Jean Sherwood Rankin, Augsburg, 1917

- The Oak by the Waters of Rowan, by Spencer Kellogg Jr, Aries Press, New York, 1927

- The Day of Doom, by Michael Wigglesworth, Spiral Press, 1929

- Pond Image and Other Poems, by Johan Egilsrud, Lund Press, Minneapolis, 1943