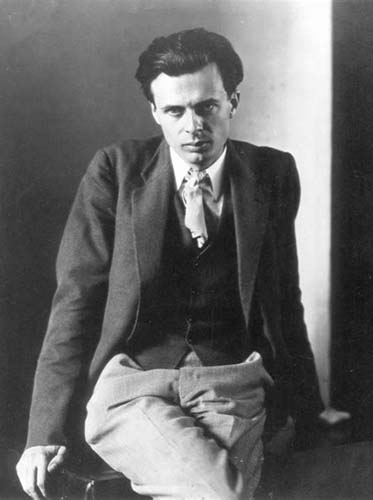

Aldous Huxley – English writer and philosopher 1894-1963

Aldous Leonard Huxley was born in Godalming, Surrey, on July 26, 1894, the third son of Leonard and Julia Arnold Huxley. It was a family of surpassing intellect and accomplishment. His father was a well-known writer, a Greek scholar, and the editor of Cornhill Magazine. His grandfather was the renowned biologist, Thomas Henry Huxley. His great-uncle was Matthew Arnold, and his aunt was the novelist, Mrs. Humphrey Ward. His older brother, Julian, was to attain fame as a biologist and writer, and his half-brother, Andrew, was a Nobel laureate in physiology.

The young Aldous survived a childhood and youth marred by several psychic bruises. His mother, to whom he was devoted, died of cancer when he was fourteen. A few years later his brother Trevenen, whom he referred to as “one that was among the noblest and best of men,” committed suicide. As a scholarship boy at Eton, after having prepared at Hillside School, Aldous developed an interest in medicine, but was frustrated in his plan to become a doctor when, at the age of sixteen, he contracted keratitis punctata, an eye disease that temporarily blinded him. He read books and music in Braille, however, and learned touch-typing; he typed out a novel, which he thought quite good, but it was lost before he or anyone else was able to read it.

Later, following surgery, he recovered sufficiently to read with one eye and a magnifying glass, but the affliction “shaped” him, he once told a friend, and “had the effect of isolating” him, and only with a formidable will was he able to surmount the handicap and even, as he said, make use of it.

Aldous Huxley’s literary career had begun in 1916 with publication of a book of verse, The Burning Wheel, and by 1920 one critic counted him “among the most promising” of the younger English poets. From early letters to his brother Julian we know he was writing verses, mostly humorous, when he was thirteen. His published poetry, contained in four volumes, the last of which appeared in 1931, is almost entirely serious, often somber, and always reflective of its author.

But it was in fiction and in his many brilliant essays that Huxley came into his own. His short stories and novels, and his excursions into journalism, brought both financial reward and fame.

In 1921 he published Crome Yellow, the first of his eleven novels; they include Antic Hay, Point Counter Point, Eyeless in Gaza, Ape and Essence, and. Brave New World. Between 1920 and 1940, Huxley published more than twenty-five books; the last, Literature and Life (1963), was his forty-fifth. The non-fiction includes The Art of Seeing, The Perennial Philosophy, Vulgarity in Literature, and two collections of travel pieces. He also edited The Letters of D. H. Lawrence, published in 1932.

Aldous Huxley spent many of his later years in America, which he once termed a “fantastic” place with “a widespread sense of insecurity.” In 1947 he settled in California, writing books and essays and turning out screen plays. Here he devoted himself to serious studies of the occult, and experimented on a very small scale with hallucinogens. He described his drug experiments in Doors of Perception (1954).

A critic once referred to all of Huxley’s work as “a curious kind of writing: writing which disguises itself as entertainment in order to interest, but which neither respects the entertainment nor believes in the instruction.” This view seems unduly harsh, ignoring as it does the clear evidence of Huxley’s abiding concern for his fellow men, his deeply compassionate outlook on a world that, though often gone wrong, always seemed worth redeeming. His life was one long campaign against wrongheadedness and stupidity. He lost his way more than once—as one is likely to do, living on a “lunatic Sphere”—but he never ceased trying to apply his brilliant mind and his enormous store of wide-ranging knowledge to the eternal problem of perfectibility, of the possibility of a better man and a better world.

Aldous Huxley continued his writing, in prodigious quantity, until his death in 1963 as a victim of cancer. His life had been complex and often frustrating, but he seemed to have no regrets. As he once put it, “I try to be sincerely myself—that is to say, I try to be sincerely all the numerous people who live inside my skin and take their turn at being the master of my fate.”

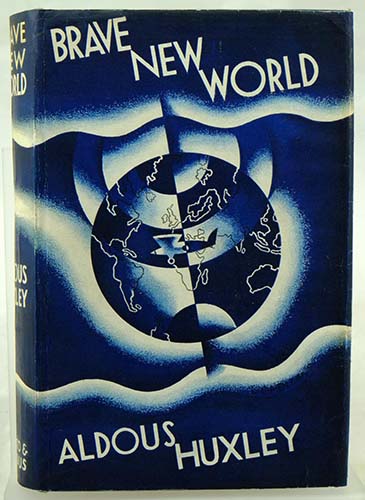

In May, 1931, Huxley mentioned in a letter: “I am writing a novel about the future —on the horror of the Wellsian Utopia and a revolt against it. Very difficult. I have hardly enough imagination to deal with such a subject. But it is nonetheless interesting work.” The novel was Brave New World, which was to reach more readers, worldwide, than any of his other works. In August he wrote to his father:

I have been harried with work—in which I have at last, thank heaven, got rid of a comic, or at least, satirical, novel about the Future, showing the appallingness (or at any rate by our standards) of Utopia and adumbrating the effects upon thought and feeling of such quite possible biological inventions as the production of children in bottles (with consequent abolition of the family and all the Freudian ‘complexes* for which family relationships are responsible), the prolongation of youth, the devising of some harmless but effective substitute for alcohol, cocaine, opium, etc.—and also the effects of such sociological reforms as Pavlovian conditioning of all children from birth and before birth, universal peace, security and stability. It has been a job writing the book and I’m glad it’s done.

Brave New World carries an epigraph, in French, by Nicolas Berdiaeff, which states: “Life is moving toward utopias. And perhaps a new age is beginning, an age in which intellectuals and people of culture will dream of the ways of avoiding utopias and returning to a non-utopian society, one less ‘perfect* and more free.”

The reader turns few pages before realizing that Huxley had, indeed, sufficient imagination to deal with his difficult subject. Nowhere is the light of his imaginative powers more fulgent than when cast on the new world’s various institutions, whose names alone reveal a brilliantly transformed dialectic.

The story is astonishingly prophetic. In his illuminating introduction to our volume, Ashley Montagu points out that “Huxley’s ‘soma,’ under the name of ‘tranquilizer,’ is today a multimillion dollar industry. That other ‘tranquilizer,’ sexual permissiveness, is also on its way to being fully realized, not to mention subliminal conditioning, hypnopaedia (teaching the sleeper), teaching machines, and all the other nefarious arts of ‘brain-washing.’ These are, already, facts of ‘civilized life.* ” And Montagu concludes: “There is an important message in Brave New World, one that is not yet too late for us to receive.”

Yet as a novel it is far from being merely clever prophecy, brilliant science-fiction, and negative utopianism. The chief characters are believable individuals whose respective shallowness, vision, frustration, or tragedy powerfully involves our emotions.

For a 1946 edition of Brave New World, Huxley wrote a Foreword in which he tells us:

All things considered, it looks as though Utopia were far closer to us than anyone, only fifteen years ago, could have imagined. Then I projected it six hundred years into the future. Today it seems quite possible that the horror may be upon us within a single century. That is, if we refrain from blowing ourselves to smithereens in the interval.

On his deathbed, unable to speak owing to advanced laryngeal cancer, Aldous Huxley made a written request to his wife Laura for “LSD, 100 µg, intramuscular.” According to her account of his death in This Timeless Moment, she obliged with an injection at 11:20 a.m. and a second dose an hour later; Huxley died aged 69, at 5:20 p.m. (Los Angeles time), on 22 November 1963.

Source: The Heritage Press, 1974.

Aldous Huxley Bibliography

Novels

- Crome Yellow (Chatto & Windus, 1921)

- Antic Hay (Chatto & Windus, 1923)

- Those Barren Leaves (Chatto & Windus, 1925)

- Point Counter Point (1928)

- Brave New World (Chatto & Windus, 1932)

- Eyeless in Gaza (Chatto & Windus, 1936)

- After Many a Summer (Chatto & Windus, 1939)

- Time Must Have a Stop (Harper & Brothers, 1944)

- Ape and Essence (Chatto & Windus, 1948)

- The Genius and the Goddess (Chatto & Windus, 1955)

- Island (Chatto & Windus, 1962)

Short Story Collections

- Limbo (1920)

- Mortal Coils (1922)

- Little Mexican and Other Stories (1924) (US title: Young Archimedes)

- Two or Three Graces and Other Stories (1926)

- Brief Candles (1930)

- Collected Short Stories (1944)

- Jacob’s Hands: A Fable (co-written with Christopher Isherwood; discovered 1997)

- After the Fireworks: Three Novellas (2016)