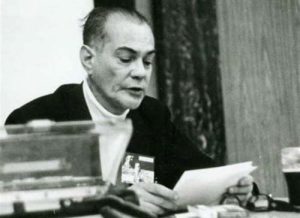

Potter, Beatrix – English Author and Illustrator, 1866-1943

Beatrix Potter’s legacy to children’s literature include; twenty-three small books and one longer collection of stories. Strict integrity to the natures of her animal characters, an ear for striking, precise language, and an eye for detail have made her stories perennial favorites since the early 1900s. Potter insisted that her books, which address children intelligently and with humor, remain inexpensive and small enough to fit in a child’s hands.

Beatrix Potter grew up in a wealthy London family. Educate by governesses and isolated in a nursery much of the time, she kept a secret menagerie of pets. At various times these included rabbits named Benjamin and Peter mice, newts, a frog, a tortoise, and a hedgehog named Mrs. Tiggy-winkle. She spent hours observing and painting her animals, immortalizing many of them later as characters in her books. Both Potter and her younger brother enjoyed drawing, although Potter did not care much for her art instructors and was mostly self-taught.

Each summer, the family rented a large house or a castle in the Lake District or in Scotland where Potter sketched the country landscapes, many of which would become the settings for her books. Throughout her life, she had passionate interests to which she devoted her full concentration. With the benefit of her considerable intelligence and perfectionism, she excelled at each. In her twenties and early thirties, for example, she was fascinated by fossils and fungi, creating detailed paintings of the specimens she collected and conducting original research in mycology. It is during this period that she developed and refined her detailed dry-brush painting style.

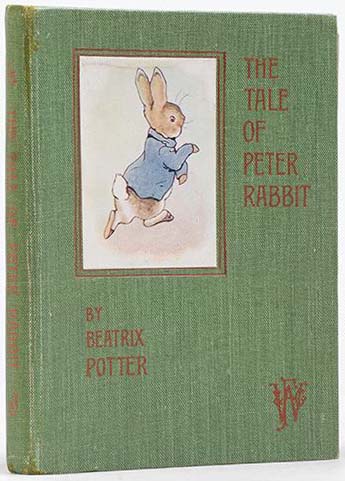

With the success of The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), when she was thirty-six, Beatrix Potter began concentrating on creating books, publishing two a year from 1902 to 1909. When the little books began to earn substantial royalties, she bought a farm in the Lake District, where she found excuses to spend more and more of her time, escaping from a stifling family situation. There, at the age of forty-seven, she married her solicitor, William Heelis. By then, her focus had begun to shift again, this time to land conservation, local antiques, and especially the breeding of Herdwick sheep, where she again achieved great success.

Although she produced nine books between 1910 and 1930, her attention was divided, and the quality of those books is uneven. For the rest of her life, she was Mrs. Heelis—sheep breeder, farmer, and landlord—and preferred to ignore her past success as Beatrix Potter. When she died in 1943, she left four thousand acres to the National Trust, including fifteen farms.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit, in which a young rabbit named Peter disobeys his mother, loses his way—and nearly loses his life—in Mr. McGregor’s garden, and finally returns to the safety of home, is one of the great success stories of children’s literature. It was first written in 1893 as an illustrated letter to Noel Moore, the five-year-old son of Potter’s friend and former governess, while he was sick. Noel, like Peter, had three sisters at that time.

When Potter tried to have it published, she was rejected by at least seven firms, and eventually decided to print it in black-and-white at her own expense. It was not until the private edition was nearly complete that Frederick Warne & Co. reconsidered its initial rejection and agreed to publish the story, provided that Potter repaint the illustrations in full color. Published by Warne in 1902, the book was an immediate success, selling 50,000 copies by the end of 1903. Peter Rabbit continues to sell at least 75,000 copies a year and has been translated into thirty languages.

Just why has Peter Rabbit been so successful? It contains, first, one of the oldest, simplest, and most compelling plots: separation from home, adventure, escape, return to home. This plot, occurring in favorite stories from Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe to Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, embodies the wishes and fears of every child. Then there is Peter. As a rabbit and a child, he is adventurous and timid, clever and incompetent, sweet and naughty.

Both text and pictures show that Peter is not a boy thinly disguised as a rabbit, but a real animal who goes “lippity-lippity” when he walks and has powerful kicking hind legs, young large ears, and sensitive whiskers. Potter’s understanding of animal anatomy, combined with her observations of animals in motion and her understanding of each animal’s nature, are channeled into her characters that readers believe instantly in the honesty and authenticity of her portrayals.

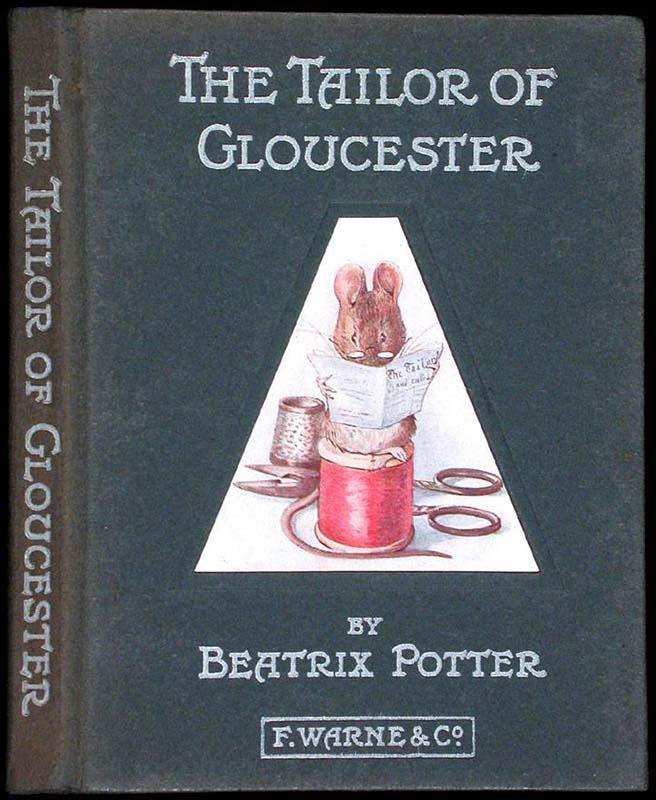

The Tailor of Gloucester (1903), Beatrix Potter’s own favorite among her books, contains her only sympathetic human character. A Christmastime favorite for many families and for library story hours, it tells of a poor tailor becomes ill before finishing the Lord Mayor’s waistcoat. The mice in the tailor’s shop take pity on him finish all but the last buttonhole, despite the malicious meddling of the tailor’s cat, Simpkin. Potter had heard this tale during a stay in Gloucester, though it was totally told as a fairy story. How much more appeal-and sensible it becomes when the fairies are replaced mice and a cat appears as their antagonist.

Some people have a mistaken impression of Beatrix eras the creator of cute animal characters in slightly sentimental stories. This could not be further from the truth. Some of her strongest characters are delightfully unsavory, like the foxy-whiskered gentleman in The Tale Jemima Puddleduck (1908), Mr. Tod and Tommy in The Tale of Mr. Tod (1912), and Samuel Whisker, the rat, in The Tale of Samuel Whiskers (1908). The importance of the food chain is just below the surface of all her stories, and she always made it clear exactly what most frightening to each animal. Surely any sentimentality is in the eye of the beholder.

She was also keenly aware of mischief and how much it can be, as in The Tale of Two Bad Mice (1904) and Tale of Samuel Whiskers. These books give an occasional nod to proper behavior for the sake of the adults, leave children with no doubt that they are really about the joys of destructive behavior.

Potter, who had been of necessity a proper, well-behaved child, intuitively understood the delight of breaking and entering, smashing dishes, and hiding from adults. In Samuel Whiskers, as in The Tale of Tom Kitten (1907) and The Tales of Pigling Bland (1913), the parents are portrayed as foolish and sometimes cruel, and the children, while disobedient, are only displaying natural behavior. Her young animals frequently shed their clothes, being more active and less concerned with appearances than their elders.

All of Beatrix Potter’s books have remained in print continuously, to the delight of generations of readers. Despite the occasional dated turn of phrase, these books seem to appeal to children of any time because they are rue to the nature of both children and the animals they portray. Potter’s respect for children’s integrity and intelligence and her intuitive understanding of child-mod fears and delights are timeless.

LOLLY ROBINSON

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.

List of Books by Beatrix Potter.