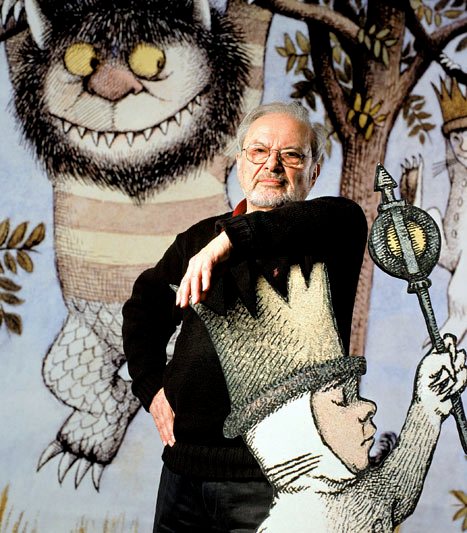

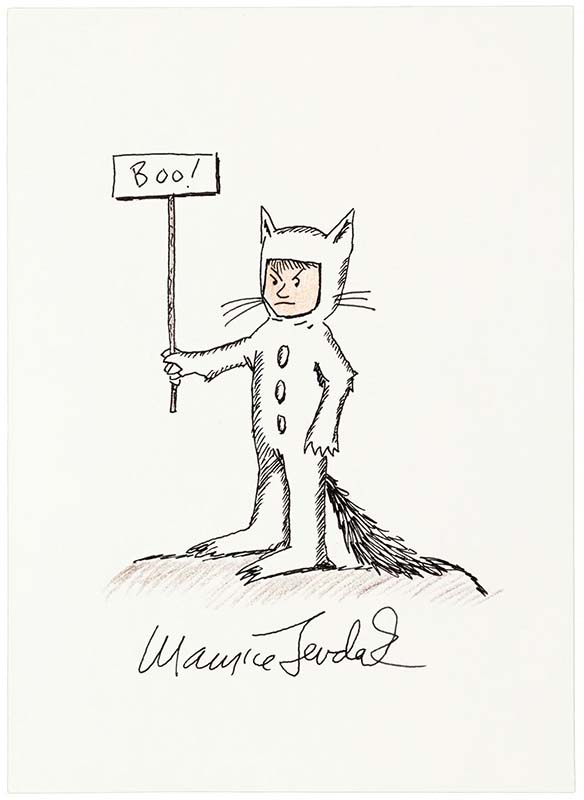

Maurice Sendak – American artist and writer, 1928-2012.

American artist and writer, 1928-2012. In the early 1960s, Brian O’Doherty, then the art critic for the New York Times, called Maurice Sendak “one of the most powerful men in the U.S.’ because of his ability to “give shape to the fantasies of millions of children—an awful responsibility.”

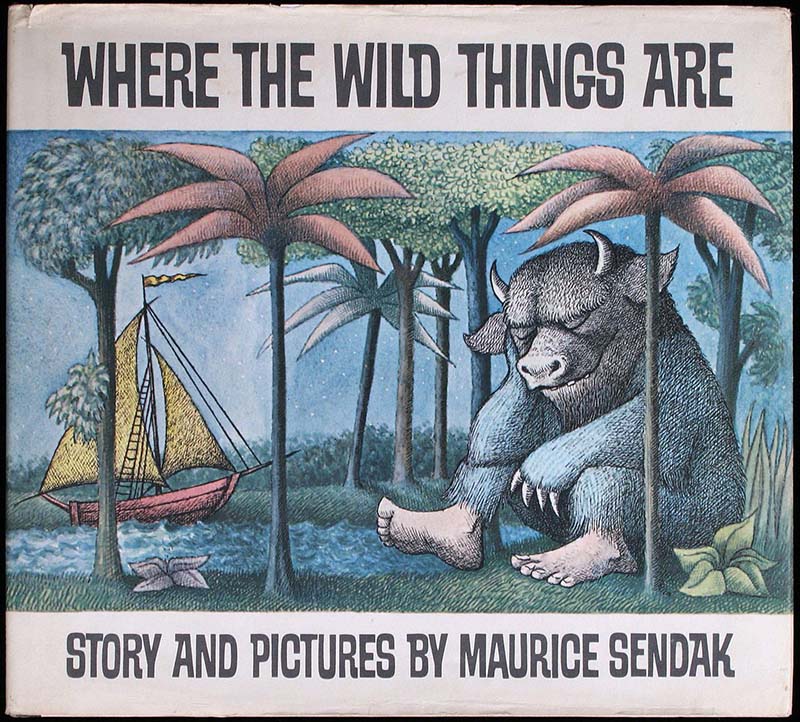

It is a challenge Sendak has continued to meet in a career that has spanned four decades and has ]ed to Sendak’s creation of the texts and illustrations for more than seventy books, which have sold tens of millions of copies in more than a dozen languages. But though Max in his wolf suit and the monsters he tames in Sendak’s classic Where the Wild Things Are (1963) have taken a permanent place in American popular culture aid the global mythology of childhood, Sendak confesses to being baffled by the acclaim his books have won.

It’s amazing I’ve had success,” he reflects, “because my books are so idiosyncratic and personal and striving for inner things rather than for outer things.”

The “inner” subject that Sendak has explored in many of his books—and what he calls his “obsession” as a writer and artist—are the fantasies that children create to combat an awful fact of childhood.” In accepting the prestigious Caldecott Medal for Where the Wild Things Are, Sendak explained this fact: “From their earliest years, children live on familiar terms with disrupting emotions…. They Continually cope with frustration as best they can. And it is through fantasy that children achieve catharsis. It is the best means they have for taming Wild Things.”

Before Where the Wild Things Are was published, Sendak had illustrated nearly fifty books written by others, many of them remarkable in their own right, like Else Holmelund Minarik’s “Little Bear” books, a memorable Series of early readers. Sendak’s first major group of pictures appeared in A Hole Is to Dig (1952), Ruth Krauss s path-breaking collection of “first definitions” that children themselves had invented to describe their world. Buttons, one definition explained, are “to keep people warm”; others reasoned that “steps are to sit on,” and rugs, of course, “ate so dogs have napkins.” To capture these fresh perceptions, Sendak set them dancing with dozens of small pen-and-ink drawings (if children.

But these were not what Sendak described as the “all- American, white-toothed” children that were so common in children’s books at the time. Instead, Sendak depicted the “hurdy-gurdy, fantasy-plagued kids” he remembered from the Brooklyn neighborhoods of the 1930s in which he Spent his childhood, the son of immigrant Jewish parents who had left little villages in Poland to come to America just before World War I. These “little greenhorns just off the boat” that Sendak drew for A Hole Is to Dig effectively began the revolution in children’s literature that Michael di Capua, one of Sendak’s editors, thinks “turned the entire tide of what is acceptable, of what is possible to put in a children’s book illustration.” Or, he might well have added, in a children’s book as a whole.

Maurice Sendak in his own words …

I was the youngest of three children growing up in Brooklyn, and when I got a book from my sister, about die last thing I did was read it. A book, to me, was for sniffing, poking, chewing, licking. The first real book I ever had was Mark Twain’s Prince and the Pauper, illustrated by Robert Lawson, whose work I still admire. I treasure that book, although I don’t know if I ever actually read it.

Children have a sensuous approach to books. I remember one letter I received from a little boy who loved Where the Wild Things Are. Actually, I think the letter was written by the boy’s mother, and he sent me a picture he had drawn. So I wrote him back and , sent him a picture. Eventually, I received another letter, this time from his mother: “Jimmy liked your postcard so much he ate it.” That letter confirmed everything I’d ever suspected.

I seem to have been blessed, or cursed, with a vivid I memory of childhood. This is not supposed to happen. According to Freud, there’s a valve that shuts off ; the horrors of childhood to make room for the horrors of adolescence. I must have a leaky valve, because I I have these torrential memories. From a career standpoint, I guess that’s been a good thing. Socially, it’s been nothing short of disaster.

I profited as a child from the dynamics of my family. My brother was a writer, and I was allowed to illustrate his stories. With alarming regularity, our ‘ home would be invaded by these galumphing people I called relatives. My brother would be called upon to i read his latest opus, and I would hold up illustrations i that I had done on shirt cardboard.

I remember one story called “They Were Inseparable” It was about a brother and sister who loved each other so much that they planned to get married. You see, Freud never came to Brooklyn. At any rate, I could understand my brother’s feelings. Our sister I was very beautiful, in a Dolores del Rio way. But he must have had a hint that this would never work, because his story ended with a terrible accident in which the brother was permanently damaged. I did very well at illustrating the blood and bandages, but not nearly so well at creating the kissing scenes.

I was a sickly child and spent a lot of time looking out the window. There was a little girl across the street named Rosie, and I must have forty sketchpads filled with Rosie pictures and Rosie stories. She was incredible. She had to fight the other kids on the block for attention, and she had to be inventive. I remember one time, when she came up with the explosive line: “Did you hear who died?” Rosie started telling the kids that she had heard a noise upstairs—a noise like someone falling, furniture breaking, and gasping, choking sounds. She went to investigate, and her grandmother was on the floor. Rosie had to give her the kiss of life—twice. Her grandmother managed to whisper “Addio Rosie” before dying. While Rosie was talking, her grandmother came up the street, carrying groceries from the market. The kids waited until she had gone into the house before turning to Rosie with the request: “Tell us how your grandma died again.”

Rosie’s stories became the basis of Really Rosie, an animated film. Then Arthur Yorinks and I formed The Night Kitchen, a children’s theater company, and we cast Really Rosie for the stage. Then we planned to collaborate on a production of Peter Pan.

J. M. Barrie left the copyright of the play with a children’s hospital in London, so I visited the hospital to ask for permission to produce the work. While I was there, I visited some of the children. You might be surprised to learn that most of the children who are terminally ill know that they are. I was asked to go see a little girl who’s dying. She had heard I was in the hospital, and since her favorite book was Where the Wild Things Are, she had asked to see me.

I sat down by her bed and started drawing. Before long, she was sitting so close to me that her face was practically on my elbow. She was saying “Put the horns on; put the teeth in” and ordering me about. She was wonderful and funny, and I drew very slowly to give her as much pleasure as possible. But after a while I became aware of something. I saw a look on her mother’s face. The girl was engrossed in the drawing, and the mother was watching her child with a look that said “How can she be so cheerful and lively when we all know …” It was a puzzled, confused, lonely look. Suddenly, without glancing up, the girl reached out until her hand touched her mother’s. Without looking, she took her mother’s hand and squeezed it. Children know everything.

My books are written for and dedicated to children like Rosie and this little girl. Children who are never satisfied with condescending material. Children who understand real emotion and real feeling. Children who are not afraid of knowing emotional truth. §

Through the 1950s Sendak went on, like his favorite composer, Mozart, to play variations on the one theme that, he believes, runs throughout his books: “how kids get through a day, how they survive tedium, boredom, how they cope with anger, frustration ” It is a subject close to his own experience in which he struggled through what he has called a “miserable” childhood. As a young boy, he was frequently 31, often desperately so—with measles, pneumonia, scarlet fever—and stuck indoors for weeks on end. But the positive effect of this isolation was that he was forced to develop his own imaginative resources; while his older siblings, Natalie and Jack, were out playing with the other kids, he “stayed home and drew pictures.”

In The Sign on Rosie’s Door (1960), Sendak gave this theme another variation when he introduced, as the book’s main character, an eight-year-old girl named Rosie. Sendak had watched and sketched the real-life Rosie from the window of his family’s Brooklyn apartment building during the summer of 1948. Recently graduated from high school, he was unemployed and trapped at home, all the while wishing he could be living across the river in Manhattan. He identified with Rosie: “She had the same problem that I had as a child in that she was stuck on a street that was probably inappropriate for her, but she’d have to make do. So, in a sense, she became the prototypical child of all my books.” In fact, this “Fellini of 18th Avenue” transformed her daily task of survival into an art form, and herself into a superstar by creating elaborate dramas and movie scripts that she “hoaxed” the neighborhood kids into acting out with her.

Sendak’s fascination with this child impresario and genius of improvisational play led him, in 1974, to do an animated television special about her (Really Rosie, Starring the Nutshell Kids), with music by another kid from Brooklyn, Carole King. And in 1981, he gave Rosie her ultimate star vehicle in the off-Broadway musical Really Rosie, which drew its characters from those who made their first appearance in Sendak’s perennially popular boxed set of four small books, The Nutshell Library (1962). Among them were Johnnie, a little boy obsessed with lurid stories he picks up about kidnappings (as it happens, one of Sendak’s own childhood fears), and Pierre, “who only could say I don’t care?” Then, of course, there is Rosie herself, who, by this time in her twenty-one-year career, can quip about how “you have to make peace with your crummy past.”

Where the Wild Things Are, though, would be Sendak’s breakthrough book. It was the first full-color picture book for which he both wrote the text and drew the pictures, and it took up, uncompromisingly and forcefully, one of those “inner things” that have continued to preoccupy Sendak’s creative life. In Max, the tantrum tossing wolf-child, Sendak portrayed what he regards as an ordinary but also “a very crucial point in a child’s life,” a dark moment when only a leap of faith into fantasy can help him find release from his rage.

Today, we are used to having around various furry, befanged descendants of the Wild Things—gobbling cookies, teaching the alphabet, or advising children about how they can cope with the dark. But when Sendak’s monsters first appeared, they were revolutionary, unexpected creatures who had sprung out of the unconscious of a child. Ordinary children were not supposed to behave that way, at least not in the public pages of a picture book. Yet Sendak asked the reader to accept Max’s behavior as just that—ordinary—and in doing so Sendak reminded us that the world of children’s fantasies is one of their best-kept secrets. Dr. Seuss’s Cat in the Hat had warned children about upsetting their parents by telling them what really went on “inside” while the adults were out. But Sendak let the cat out of the bag.

Other books that followed Wild Things took Sendak farther into the territory that the psychologist James Hillman refers to as “the dark side of the bambino.” In the Night Kitchen (1970) spun the reader through the surreal fantasy of a child’s dream, like Alice into Wonderland or Dorothy into Oz. Mickey, the hero of this voyage into the unconscious, is popped into an oven by three giant, Oliver-Hardy bakers before he can escape in an airplane that he fashions from dough and fly off to find the missing ingredient for morning cake.

While the book was, in part, Sendak’s homage to New York City and the movies of the 1930s that had so affected him as a child (among them Disney’s early Mickey Mouse cartoons, King Kong, and Busby Berkeley’s musicals), it was also a celebration of the primal, sensory world of childhood and an affirmation of its imaginative potency. The jubilant point that Sendak makes about our naked human nature continues to transcend the controversy that may arise as a result of Sendak’s having let Mickey fall out of his bed and out of his pajamas across the pages of his adventure.

About ten years later, Outside Over There (1981), the third book in what Sendak considers is his trilogy of works that deals specifically with that “inner” theme, took up the fantasy of a little girl, Ida, who is stuck looking after her baby sister. For an instant, Ida ignores the infant and plays her wonderhorn instead. In that brief moment, the baby is stolen by goblins and Ida must imagine a way to recover the infant. Sendak chose the late eighteenth century as the setting for the book, the time of the Brothers Grimm (whose tales Sendak has illustrated in his 1973 collection, The Juniper Tree done with translator Lore Segal) and of Sendak’s favorite artist, Mozart. But though he places the book in the past, Sendak is again dealing with the complex emotional life of children in through their fantasies.

Sendak believes that “his most unusual gift is that [his] child self seems still to be alive and well” and that he can continue to remain closely in touch with this source of creative energy. But there are some risks, he notes: “Reaching back to childhood is to put yourself in a state of vulnerability again because being a child was to be so. But then all of living is so—to be an artist is to be vulnerable.”

Sendak has continued to take these creative chances himself, beginning a second career in the 1980s as a designer for ballet and opera, gathering rave reviews for this new work that now ranges from Mozart’s Magic Flute and Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker to a double bill of two short fantasy operas based on Where the Wild Things Are and another Sendak book, Higglety-Pigglety Pop! (1967). There also have been other book projects, including his powerful paintings for a hitherto unpublished Grimm’s tale, Dear Mili (1988), and his spirited, playful drawings (reminiscent of those that began his career) for the children’s folklore collected by Iona and Peter Opie in I Saw Esau (1992).

Sendak has continued to draw on the rich interpretative possibilities of folk rhymes in his most recent picture book, We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy (1993). The text for this work comes from two obscure Mother Goose rhymes whose meaning had puzzled Sendak, he reports, since the 1960s when he first came across them while working on a possible collection of nursery rhymes. He was finally able to make sense of these verses when he saw that they could be used to illustrate the problem of the homeless, impoverished, violent conditions in which so many children today are forced to live. In the book that has emerged from this fusion of die archaic with his impassioned, contemporary vision, Sendak finds the happiest ending that he can for his abandoned kids: in a world that is indifferent—indeed, hostile—to their needs, they end up taking care of one another. In the process they claim for themselves a moving, transcendent power—one based on compassion and community.

The 1990s are offering Sendak other new directions in his creative drives, taking him to Hollywood, where he is in the process of developing a number of his projects as films, and back to the dramatic stage, as the founding force, with Arthur Yorinks, of the Night Kitchen Theater. The innovative national touring company has begun to produce original dramatic works by, among others, Yorinks and Sendak.

Though Sendak does not have any actual children, he remains extremely close to those creative offspring who have appeared in his books. Every year, Sendak reports, dozens of schools and children’s groups ask him for permission to stage their own versions of Where the Wild Things Are, often with a girl playing Max, a gender breaking change in his text that delights him. And every year, he says, he can hardly hold back the tears when “parents who were little people when I wrote the book present their children to me. And here are these new human beings with their eyes beaming, and they are again in wolf suits.”

§ John Cech

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.

Maurice Sendak Works

As author and illustrator

- Kenny’s Window (1956)

- Very Far Away (1957)

- The Sign on Rosie’s Door (1960)

- The Nutshell Library (1962)

- Alligators All Around

- Chicken Soup with Rice

- One Was Johnny

- Pierre

- Where the Wild Things Are (1963)

- Let’s Be Enemies (written by Janice May Udry) (1965)

- Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life (1967)

- In the Night Kitchen (1970)

- Fantasy Sketches (1970)

- Ten Little Rabbits: A Counting Book with Mino the Magician (1970)

- Some Swell Pup or Are You Sure You Want a Dog? (written by Maurice Sendak and Matthew Margolis, and illustrated by Maurice Sendak) (1976)

- Seven Little Monsters (1977)

- Outside Over There (1981)

- Caldecott and Co: Notes on Books and Pictures (an anthology of essays on children’s literature) (1988)

- The Big Book for Peace (1990)

- We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy (1993)

- Maurice Sendak’s Christmas Mystery (1995) (a box containing a book and a jigsaw puzzle)

- Bumble-Ardy (2011)

- My Brother’s Book (2013)

As Illustrator

- Atomics for the Millions (by Maxwell Leigh Eidinoff, 1947)

- The Wonderful Farm (by Marcel Aymé, 1951)

- Good Shabbos Everybody (by Robert Garvey, 1951)

- A Hole is to Dig (by Ruth Krauss, 1952)

- Maggie Rose: Her Birthday Christmas (by Ruth Sawyer, 1952)

- A Very Special House (by Ruth Krauss, 1953)

- Hurry Home, Candy (by Meindert DeJong, 1953)

- The Giant Story (by Beatrice Schenk de Regniers, 1953)

- Shadrach (by Meindert Dejong, 1953)

- I’ll Be You and You Be Me (by Ruth Krauss, 1954)

- The Tin Fiddle (by Edward Tripp, 1954)

- The Wheel on the School (by Meindert DeJong, 1954)

- Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s Farm (by Betty MacDonald, 1954)

- Charlotte and the White Horse (by Ruth Krauss, 1955)

- Happy Hanukah Everybody (by Hyman Chanover and Alice Chanover, 1955)

- Little Cow & the Turtle (by Meindert DeJong, 1955)

- Singing Family of the Cumberlands (by Jean Ritchie, 1955)

- What Can You Do with a Shoe? (by Beatrice Schenk de Regniers, 1955, re-colored 1997)

- Seven Little Stories on Big Subjects (by Gladys Baker Bond, 1955)

- I Want to Paint My Bathroom Blue (by Ruth Krauss, 1956)

- The House of Sixty Fathers (by Meindert De Jong, 1956)

- The Birthday Party (by Ruth Krauss, 1957)

- You Can’t Get There From Here (by Ogden Nash, 1957)

- Little Bear series (by Else Holmelund Minarik)

- Little Bear (1957)

- Somebody Else’s Nut Tree (1958)

- Father Bear Comes Home (1959)

- Little Bear’s Friend (1960)

- Little Bear’s Visit (1961)

- A Kiss for Little Bear (1968)

- Circus Girl (by Jack Sendak, 1957)

- Along Came a Dog (by Meindert DeJong, 1958)

- No Fighting, No Biting! (by Else Holmelund Minarik, 1958)

- What Do You Say, Dear? (by Sesyle Joslin, 1958)

- Seven Tales by H. C. Andersen (translated by Eva Le Gallienne, 1959)

- The Moon Jumpers (by Janice May Udry, 1959)

- Open House for Butterflies (by Ruth Krauss, 1960)

- Best in Children’s Books: Volume 31 (various authors and illustrators: featuring, Windy Wash Day and Other Poems by Dorothy Aldis, illustrations by Maurice Sendak, 1960)

- Dwarf Long-Nose (by Wilhelm Hauff, translated by Doris Orgel, 1960)

- Best in Children’s Books: Volume 41 (various authors and illustrators: featuring, What the Good-Man Does Is Always Right by Hans Christian Andersen, illustrations by Maurice Sendak, 1961

- Let’s Be Enemies (by Janice May Udry, 1961)

- What Do You Do, Dear? (by Sesyle Joslin, 1961)

- The Big Green Book (by Robert Graves, 1962)

- Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present (by Charlotte Zolotow, 1962)

- The Singing Hill (by Meindert DeJong, 1962)

- The Griffin and the Minor Canon (by Frank R. Stockton, 1963)

- How Little Lori Visited Times Square (by Amos Vogel, 1963)

- She Loves Me … She Loves Me Not … (by Robert Keeshan, 1963)

- Nikolenka’s Childhood: An Edition for Young Readers (by Leo Tolstoy, 1963)

- McCall’s: August 1964, VOL. XCI, No. 11 (featuring The Young Crane by Andrejs Upits, illustrations by Maurice Sendak, 1964)

- The Bee-Man of Orn (by Frank R. Stockton, 1964)

- The Animal Family (by Randall Jarrell, 1965)

- Hector Protector and As I Went Over the Water: Two Nursery Rhymes (traditional nursery rhymes, 1965)

- Lullabyes and Night Songs (by Alec Wilder, 1965)

- Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories (by Isaac Bashevis Singer, 1966)

- The Golden Key (by George MacDonald, 1967)

- The Bat-Poet (by Randall Jarrell, 1967)

- The Saturday Evening Post: May 4, 1968, 241st year, Issue no. 9 (features Yash The Chimney Sweep by Isaac Bashevis Singer, 1968)

- The Light Princess (by George MacDonald, 1969)

- The Juniper Tree and Other Tales from Grimm: Volumes 1 & 2 (translated by Lore Segal with four tales translated by Randall Jarrell, 1973 both volumes)

- King Grisly-Beard (by the Brothers Grimm, 1973)

- Pleasant Fieldmouse (by Jan Wahl, 1975)

- Fly by Night (by Randall Jarrell, 1976)

- Mahler – Symphony No. 3, James Levine conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra – album cover artwork “What The Night Tells Me”, 1976

- The Big Green Book (by Robert Graves, 1978)

- Singing family of the Cumberlands (by Jean Richie, 1980)

- Nutcracker (by E.T.A. Hoffmann, 1984)

- The Love for Three Oranges (The Glyndebourne version, by Frank Corsaro, based on L’Amour des Trois Oranges by Serge Prokofiev, 1984)

- In Grandpa’s House (by Philip Sendak, 1985)

- The Cunning Little Vixen (by Rudolf Tesnohlidek, 1985)

- The Mother Goose Collection (by Charles Perrault with various illustrators, 1985)

- Dear Mili (written by Wilhelm Grimm, 1988)

- Sing a Song of Popcorn: Every Child’s Book of Poems (by Beatrice Schenk de Regniers with various illustrators including Maurice Sendak, 1988)

- The Big Book for Peace (various authors and illustrators, cover also by Maurice Sendak, 1990)

- I Saw Esau (edited by Iona Opie and Peter Opie, 1992)

- The Golden Key (by George MacDonald, 1992)

- We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy: Two Nursery Rhymes with Pictures (traditional nursery rhymes, 1993)

- Pierre, or The Ambiguities: The Kraken Edition (by Herman Melville, 1995)

- The Miami Giant (by Arthur Yorinks, 1995)

- Frank and Joey Eat Lunch (by Arthur Yorinks, 1996)

- Frank and Joey Go to Work (by Arthur Yorinks, 1996)

- Penthesilea (by Heinrich von Kleist, 1998)

- Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom (by Ursula Nordstrom, 1998)

- Swine Lake (by James Marshall, 1999)

- Brundibár (by Tony Kushner, 2003)

- Sarah’s Room (by Doris Orgel, 2003)

- The Happy Rain (by Jack Sendak, 2004)

- Pincus and the Pig: A Klezmer Tale (performed by the Shirim Klezmer Orchestra and narrated by Maurice Sendak, 2004)

- Bears! (by Ruth Krauss, 2005)

- Mommy? (by Arthur Yorinks, Maurice Sendak’s only pop-up book, 2006)

- Bumble Ardy, illustrated and written by Maurice Sendak, (2011)

- My Brother’s Book, illustrated and written by Maurice Sendak (Released posthumously, February 5, 2013)

- Presto and Zesto in Limboland (by Arthur Yorinks and Maurice Sendak, released posthumously, September 4, 2018)