Edmund Dulac -Illustrator and stamp designer, 1882-1953.

Edmund Dulac (born Edmond Dulac; 22 October 1882 – 25 May 1953) was a French British naturalised magazine illustrator, book illustrator and stamp designer. Born in Toulouse he studied law but later turned to the study of art at the École des Beaux-Arts. He moved to London early in the 20th century and in 1905 received his first commission to illustrate the novels of the Brontë Sisters. During World War I, Dulac produced relief books and when after the war the deluxe children’s book market shrank he turned to magazine illustrations among other ventures. He designed banknotes during World War II and postage stamps, most notably those that heralded the beginning of Queen Elizabeth II’s reign.

As illustrator of Deluxe gift books during the first two decades of the twentieth century, both Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac inherited what the industrial age had made possible the generation before. Never before had the climate been so ideal for the creation of exquisitely manufactured luxury items. The industrial revolution had produced the technical means of reproducing colorful paintings and an acquisitive market to which these stunning objects could be sold. Children’s books were now items of beauty to be collected by adults, emblems of affluence and good taste.

In the period between 1905 and World War One, gift book publishing was big business. Because Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac were the most eminent illustrators of gift books, their names are often linked, just as Walter Crane, Kate Greenaway, and Randolph Caldecott had been linked twenty-five years earlier for their contributions to the burgeoning market in children’s books. Like their three predecessors, Dulac and Rackham also had much in common. Rival publishers competed for their services and the two artists exhibited original paintings at the same gallery with equal success. Even the stories they illustrated were similar, appealing to the prevailing ardor for stories about fairies and fantasy. In spite of what they shared, however, Dulac and Rackham differed greatly in technique, temperament, and sensibility.

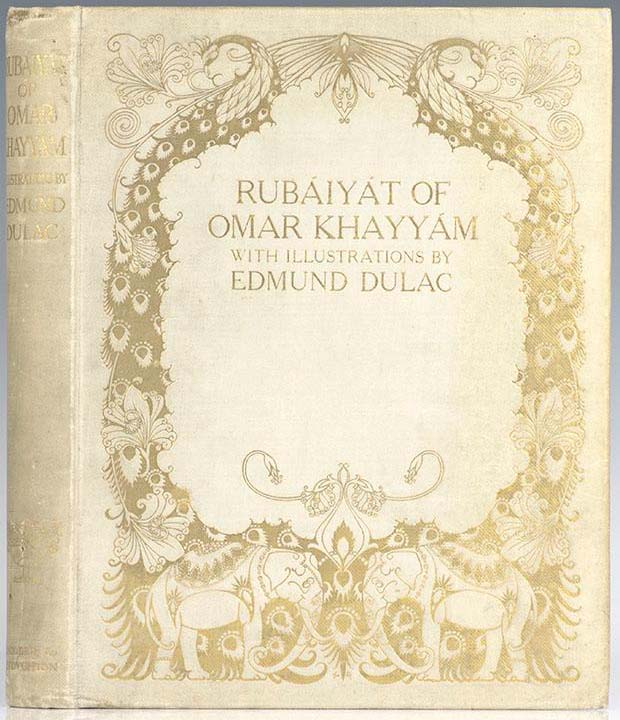

Although the two illustrators painted in watercolor, for example, Dulac was a colorist fascinated above all with pigment and pattern, while Rackham’s passion was for line. For subject matter Rackham seemed to reach more deeply into Nordic and Teutonic mythology, his brush inspired by images of dark forests inhabited with gnomes and goblins. Dulac, on the other hand, was intrigued by Eastern traditions, his imagination fired by brightly jeweled patterns that radiated in sparkling color. Although they both illustrated many of the same stories, Rackham’s style seemed more suited to Richard Wagner and to the Brothers Grimm, while Dulac was more in tune with The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and The Arabian Nights. Not surprisingly, Arthur Rackham was firmly rooted by breeding and conviction in northern traditions—an Englishman, through and through—while Edmund Dulac was an expatriated Frenchman, drawn toward mysticism and the occult, with a fascination for the exotic.

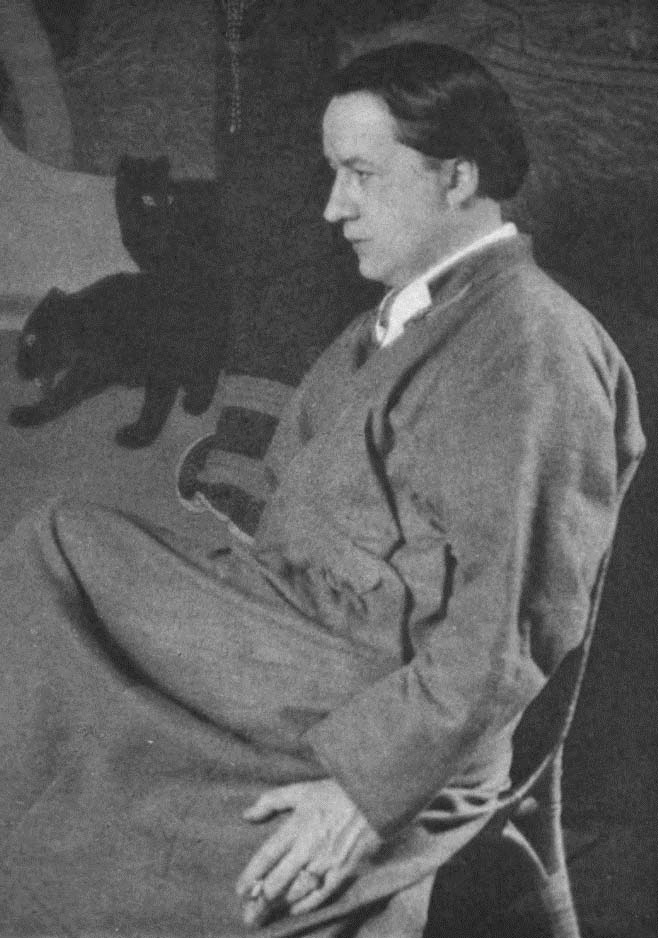

Before he reached the age of thirty Dulac was among the most highly sought-after illustrators in the world, but the journey to success took several twists and turns, and brought him a considerable distance from where he started. From the beginning, he seemed out of place with his native French heritage. Dulac was born in 1882 as Edmond (spelled with an “o”) in Toulouse where his petit- bourgeois parents kept a modestly comfortable home. The boy’s interest in painting derived from his father, a traveling salesman who restored and traded in paintings during leisure hours and created a watercolor of his own now and then.

Although Edmond liked to paint and draw from a very early age, it was not until he was fifteen that his efforts began to outrank those of his peers at school. Because it was unthinkable that Edmond should make a career as an artist, his parents allowed him to study art in the evenings at the nearby Ecole des Beaux Arts only if he agreed to study law during the day at Toulouse University. He endured this program for two full years, submitting designs to various magazines in the hope that he might be rescued from his plight as a law student. To his delight, the designs were received warmly by publications in Toulouse and in Paris and when he won a significant prize at the Ecole for his painting, he abandoned the insufferable law studies to attend art school full time.

Dulac’s hard work as an art student earned him several awards during his three-year course of studies at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and finally a scholarship to study at the prestigious Academic Julian in Paris. With great expectations, Dulac ventured to Paris to study at the famous school where the great designer Alphonse Mucha had studied and where Kay Nielsen would eventually enroll. But the program was a disappointment. Tediously copying master paintings and plaster casts did little to stimulate the impatient young artist and he felt exceedingly lonely in Paris. Returning to Toulouse in an unhappy state of mind, Dulac met and hastily married an American woman thirteen years his senior, a union that terminated almost as quickly as it had begun. At twenty-one, alone again and living with his parents, Edmund Dulac seemed very far from achieving his goals.

Edmund Dulac yearned to go to England, but decided to launch his career in the more familiar city of Paris instead. Once he found himself back in the city he had abandoned less than two years earlier, however, the restless young man decided to move on, to satisfy his yearnings by taking a daring leap to London in search of assignments. It was either good fortune or demonstrable talent that earned him a major assignment within weeks of his arrival in London: the publisher J. M. Dent commissioned him to prepare sixty watercolors for the complete set of novels written by the Bronte sisters.

His first assignment was Jane Eyre, to be published in 1905. That the neophyte Frenchman completed twelve watercolors depicting a thoroughly British subject (and did so within a period of only three months) was evidence of Dulac’s eagerness to succeed. The illustrations for the Bronte novels may have been timid, not unlike much of what was currently being published, but they were cordially received by the critics and Dulac felt sufficiently encouraged to remain in England.

As a result of the favorable reception to the Bronte novels., Dulac was invited to contribute to the Pall Mall Gazette, a monthly magazine to which Arthur Rackham had contributed many drawings. Here Dulac felt free to experiment with his designs, overcoming the timidity of his first assignments. Joining the London Sketch Club also gave him the opportunity to develop the worthwhile skill for humorous drawing. By 1906 Edmund Dulac was confident and capable, ready to take on a major challenge.

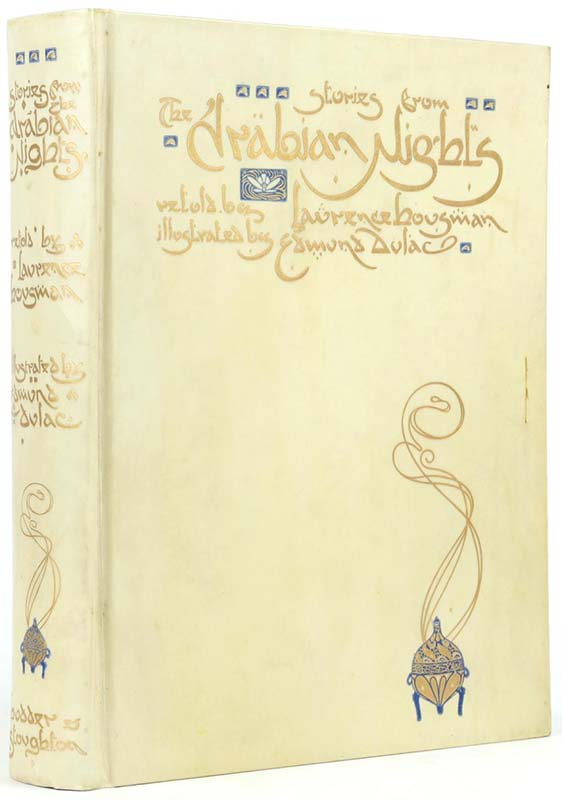

As it happened, the time was ideal for a man of Dulac’s particular talent for watercolor. Only the year before, Arthur Rackham had achieved great success with his watercolor illustrations prepared for a gift book entitled Rip Van Winkle. Simultaneously with the publication of this book, Leicester Galleries had exhibited Rackham’s original illustrations and nearly all were sold. A second Rackham exhibition and publication, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, promised to be even more successful. In the hope that Leicester Galleries might consider taking on another artist of merit, Dulac presented his portfolio to the directors. The gallery was extremely impressed with his work and made an unusual offer: they would assume responsibility for publishing a book with Dulac’s illustrations and the artist would provide fifty watercolors, including their copyright, to the gallery in exchange for a flat fee. Dulac happily agreed to illustrate the stories from The Arabian Nights.

Meanwhile, there were two London publishers competing for the gift book market—William Heinemann and Hodder & Stoughton. When Arthur Rackham eventually decided to sign on with Heinemann, Hodder & Stoughton immediately set out to find a suitable rival, and was thrilled with the candidate proposed by Leicester Galleries. The Arabian Nights, they agreed, would be an ideal gift book for the following Christmas, 1907, and the publishers felt confident that their book with illustrations by Edmund Dulac would stand up well against Rackham’s next production, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

As it turned out The Arabian Nights could not have been a better choice. To Dulac, it provided a vehicle for depicting the exotic subjects he preferred. Since art school he had been fascinated by the East and by Arabic languages, intrigued by the designs of the written Arabic characters. The nocturnal scenes in The Arabian Nights also enabled him to experiment with rich shadings of blues—ultramarine, Prussian blue, indigo, violets, and purples—permitting him to create magical, translucent textures, starry nights sparkling with saturated water color pigments.

The watercolors were to be reproduced in three colors—yellow, red, blue—inks which would be overlaid onto a black key plate. For this process, Dulac’s suffused watercolor technique was well- suited. In reproduction the initial ink drawing was essentially covered by three successive layers of printing inks, transforming the ink line into one that was no longer truly black, and happily muting it at the same time. The softness of Dulac’s illustrations was, therefore, enhanced by the reproduction process itself, and contributed to Dulac’s reputation as a supreme colorist.

Leicester Galleries displayed the Dulac watercolors for The Arabian Nights in the autumn of 1907, at the same time the book was released. With unanimous praise the book was received by the critics and every picture sold even before the exhibition was opened to the general public. In light of this overwhelming success, Leicester Galleries promptly signed a contract with Dulac for one book a year, the subject to be chosen jointly between them and in consultation with Hodder & Stoughton. Although it was an unorthodox arrangement— Dulac was accountable to the gallery, rather than to the publisher—these terms permitted the artist to concentrate his creative energies on painting, unencumbered with the technical problems of production and printing.

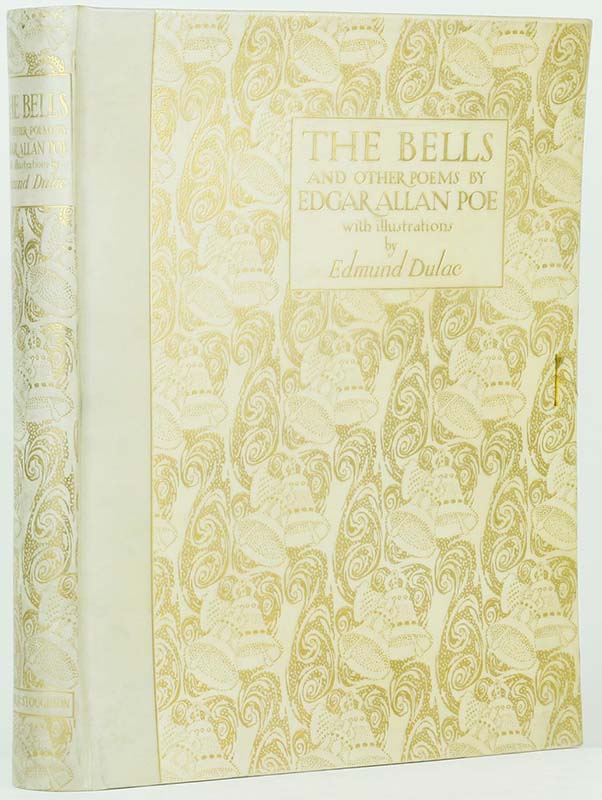

Having had the good sense to commission this young, relatively unknown illustrator, Leicester Galleries reaped the rewards of their foresight during the years that followed. Dulac would come to regret the flat-fee arrangement—he received no royalties from the sale of the gift books published by Hodder & Stoughton—but within five years he was one of the most highly paid illustrators of his time. Each year, until World War One erupted, Dulac created watercolors for a book and an exhibition at the gallery, preparing from a maximum of fifty watercolors (Arabian Nights’) to a minimum often (Princess Badoura). Dulac’s gift book for 1908 was Tempest; for 1909, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam; for 1910, The Sleeping Beauty and Other Fairy Tales; for 1911, Stories from Hans Andersen; for 1912, Bells and Other Poems by Edgar Allan Poe; for 1913, Princess Badoura; for 1914, Sinbad the Sailor and Other Stories from The Arabian Nights.

These gift books, representing Dulac’s classic contributions to the illustration of children s stories, demonstrate the evolution of the artist s style. From the outset, Dulac’s penwork was used primarily to define figures and objects, while color was employed to create atmosphere and modeling. Unlike his contemporaries Arthur Rackham and Kay Nielsen, Dulac’s drawing was secondary to color and as his work developed he became increasingly absorbed in matters of pattern and texture rather than contour.

Always intrigued by Eastern cultures, Dulac was particularly fascinated with Persian miniatures and incorporated many Persian elements into his own work. Dulac’s palette became brighter, resembling the enamel-like colors of the Persian miniatures as he turned to tangerine and carmine hues placed against large pastel color areas created by the addition of Chinese white to his watercolor pigments.

Like his palette, Dulac’s composition also evolved as a result of his close study of the Persian miniatures: flat planes arranged in patterns, simplified shapes placed on a jeweled surface. With his extended color range, Dulac now took even greater delight in creating rich patterns on robes and draperies. In the later books, he liberated himself from the conventional perspective of Western art, concerned instead with juxtaposing shapes and color in pleasing patterns. He no longer directed the eye into a perspective view. Instead, he employed a high vantage point, manipulating perspective from above and below as he saw fit, so that the eye must scan the entire picture plane to receive all the visual information presented. Depth was reduced by tilting floors forward and by eliminating any differences in color or size between objects in the background and those in the foreground.

Although his style evolved over the years, Dulac’s methods of preparing his illustrations remained the same. It was an unusual technique that worked well for him because of his concern with pictorial arrangement. He began by using tracing papers to develop his first rough sketch. “An idea for the composition is roughed out on a sheet of tracing paper with a B pencil,” Dulac explained when asked how he prepared his watercolors, and another and another, the paper being turned over from time to time to see whether the design does not look better from the other side.

One could go on like that for ever, but one of the designs has to be chosen—it is generally the first. The figures are drawn to the required size separately; a dozen rough, sketches o r so for each, this time with a BB pencil and traced over again until clean lines emerge from out of chaos. The background comes last and is dealt with in the same way. The process so far is secret. No one is allowed to witness its laborious steps and the wastepaper basket in the summer and the stove in winter take care that no evidence of it shall remain. The clean tracings are then superimposed and twisted about until some form of satisfactory arrangement is obtained.

From the time he arrived in London as a twenty- two-year-old Frenchman until World War One, Edmund Dulac was set on a course that finally seemed suited to his ambition. He was legally divorced from his American wife in 1908, married Elsa Amalice Bignardi in 1911, and became a naturalized British citizen in 1912. Dulac’s circle of friends widened to include eminent artists, writers, musicians, and designers, and he was able to pursue his intense curiosity about a wide variety of subjects: he was a student of Far Eastern music, a collector of Oriental paintings, a gourmet cook, a skilled hand book-binder, a marksman, and he designed all the furniture and equipment in his studio.

In 1914 Leicester Galleries offered Dulac a three-year contract to prodece annually a set of illustrations for books to be published in 1915, 1916, and 1917, For nearly £1,000 per set (a sizable sum), Dulac would prepare twenty-five illustrations and additional decorations for books whose titles would be agreed upon by the two parties in consultation with Hodder & Stoughton. The generosity of the terms expressed optimism about the future of gift book publishing, but the outbreak of war shattered these hopeful plans. Restrictions on paper and production curtailed a good deal of publishers’ commercial activities, and preference was given instead to publishing designed to promote the war effort.

To raise funds, for example, prominent personalities had begun to sponsor the publication of books, the proceeds from which would be sent to a cause selected by the sponsor. Contributing to these inexpensive gift books were famous writers and artists. In this capacity, Dulac offered his services, creating illustrations for three such sponsored books published by Hodder & Stoughton: Princess Mary’s Gift Book, King Albert’s Book, and Edmund Dulac’s Picture-book for the French Red Cross.

With his income severely reduced during the War, Dulac fell into a state of despair and anxiety. Leicester Galleries came to his relief in 1915 by commissioning him to prepare a set of illustrations for a book of fairy tales. Published in 1916, Edmund Dulac’s Fairy Book—Fairy Tales of the Allied Nations, represented a real tour de force for the illustrator. For each fairy tale, Dulac adapted his style to that of each country included—Japan, Serbia, Italy, Belgium, France, England, and Russia—demonstrating his profound empathy with a variety of different ages and cultures.

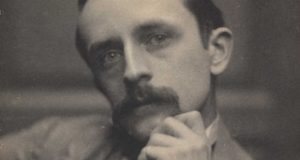

The War years continued to be extremely difficult for Dulac. He had a serious accident, almost losing the sight in one eye when his cat, in play, scratched the right cornea. The blackouts each night in London, the constant threats of bombing raids over their home, proved too great a strain for his wife and she suffered from frequent anxiety attacks and depression. There were a few respites from these tense years. Dulac was given the opportunity to design costumes and sets for Thomas Beecham’s production of a stage version of Bach’s cantata, Phoebus and Pan in 1915 and in 1916 he collaborated with his good friend, the poet W.B. Yeats, in a production of chamber plays called At the Hawk’s Well, designing costumes, props, and makeup, and even composing the music for Yeats’ plays, ha 1916 the New York art gallery of Scott & Fowles exhibited Dulac’s work (they later exhibited Arthur Rackham as well) and Hodder & Stoughton commissioned him to prepare Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Tanglewood Tales for publication. For this project, Dulac made fourteen watercolors, completed in 1917, although publication was delayed until 1918 because of paper restrictions. This was the last of the Edmund Dulac-Hodder & Stoughton gift books. An era of publishing had come to an end.

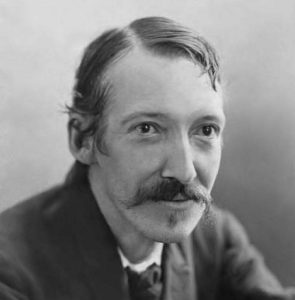

When Arthur Rackham encountered the same diminishing demand for deluxe picture books in England, he planned his books for the more receptive American market, continuing to produce illustrated books—many of them for children —nearly every year for the rest of his life. Edmund Dulac turned his talents to other forms of design instead. Except for one or two books in the 1920s (most notably Treasure Island, which was his favorite), Dulac no longer illustrated stories that might be read by children. He illustrated adult fiction, including poetry written by his friend W.B. Yeats or novels by his lover and companion Helen Beauclerk (Dulac and his wife Elsa had separated in 1923).

The major source of his income (which was sporadic at best) derived from portrait commissions, humorous caricatures, and above all his regular contributions to the magazine American Weekly. The major sources of his interest, however, derived from designing postage stamps, as well as his designs of costumes and stages for the theater. He also applied his remarkable skills to designing playing cards, banknotes, coins and medals, and found this fascinating as well. He even designed furniture for a smoking lounge in the Canadian Pacific ocean liner The Empress Britain! Nor were all his activities restricted to design. Dulac composed music and became actively engaged in a movement to help obtain recognition for the cinema as an art form.

Until his death in 1953, Edmund Dulac remained vital and active, an intellectual with boundless curiosity about all cultures, expressed in all forms— writing, pictures, music, costumes. His curiosity extended even beyond earthly phenomena, as he grew increasingly interested in spiritualism. Dulac’s pictures for children’s stories were created within only a few years of his productive life, but they continue to delight children even today. In the end, the efforts of Edmund Dulac to transcend geographic and spiritual Emits brought forth a legacy for children that remains eternal.

Susan E. Mayer – A Treasury of the Great Children’s Book Illustrators.