Share via:

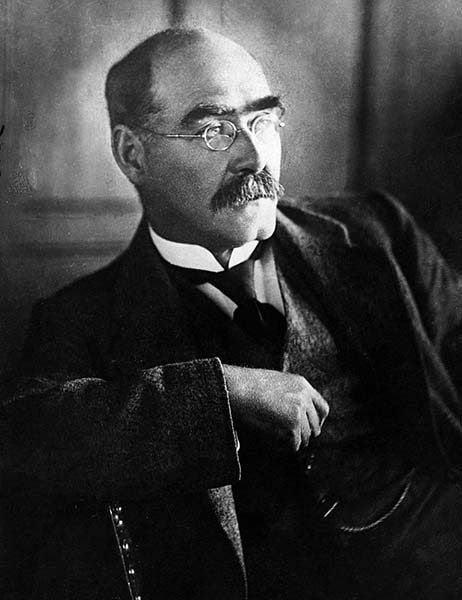

Rudyard Kipling – English journalist, short-story writer, poet, and novelist 1865-1936

The works of Rudyard Kipling, who in 1907 became the first English writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize, have left a mixed legacy: Kipling is recognized for his extraordinary ear for language, his precise use of spare, vivid imagery, and his innovative plots and deceptively simple structure.

He has also been accused of vulgarity, sentimentality, and copiousness and has been identified with imperialism, jingoism, fascism, and racism. Critics and proponents alike, however, tend to agree that Kipling’s most uncontroversial achievements are his children’s stories.

Born in India of English parents, Joseph Rudyard Kipling spent the first years of his life speaking Hindustani and living in a bungalow. At age six, he was taken to England to board with an unsympathetic foster family, a miserable experience he later wrote about in “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep,” one of the short stories in Wee Willie Winkie (1888).. In 1878 he entered an inferior boarding school and later fictionalized his schoolboy days in Stalky and Co. (1899) . By the time Kipling was twenty-five, he had traveled back and forth from England to India and had over seventy short stories, poems, and novels in print. Marriage to an American woman brought Kipling to Brattleboro, Vermont, where he wrote some of his best children’s stories.

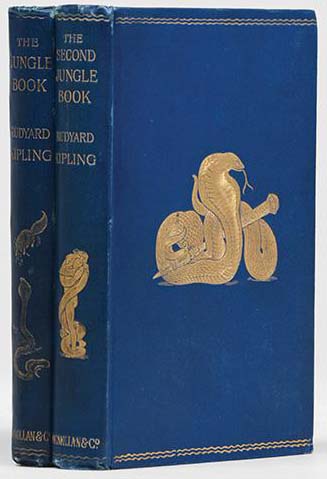

The Jungle Book (1894.) and its sequel The Second Jungle Book (18’95?) chronicle, in both narrative and verse, the adventures of a human boy, Mowgli, who is raised by wolves and instructed in the legend and lore of the Jungle by Baloo the bear and Bagheera the panther. The Jungle Books are replete with adventure and excitement—Mowgli swings from the treetops with the Bandar-log (monkeys), he wrestles with Kaa the giant python, he discovers jewels guarded by the White Cobra. There is also conflict and a strict sense of law and order in Kipling’s jungle: “Now this is the Law of the Jungle—as old and as true as the sky; And the Wolf that shall keep it may prosper, but the Wolf that shall break it must die.’’

The lessons Mowgli learns from the Jungle people serve him when he is exiled to the superstitious world of man. The outsider Mowgli served as a prototype for Kipling’s most famous hero, Kim, in the novel Kim (1901): Kimball O’Hara, an Irish orphan, is raised in India and “adopted” by a lama, (holy man) from Tibet who is on a quest for the mystic River of Arrows. Kim’s intimate knowledge of India makes him a valuable asset to the English Secret Service, and he soon distinguishes himself by capturing the papers of Russian spies. While Kim has been criticized for the young protagonist’s lack of introspection, the book presents a vivid portrait of India, its teeming populations, and it superstitions, and it is generally considered Kipling’s masterpiece.

In 1896 Rudyard Kipling returned to England, where he wrote Just So Stories (1902). The stories gave humorous accounts of the development of certain animals’ physical characteristics: “How the Camel Got His Hump” tells of a camel who hawed and humphed so often that his humph was transformed into a hump; “The Elephant s Child” explains how a baby elephant stretched his nose into a trunk while trying to free himself from the mouth of a crocodile. Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906), illustrated by Arthur Rackham and Rewards and Fairies (1910), collections of tales inspired by his house in the English countryside, followed. After this last book, Kipling stopped writing specifically for children—the death of his daughter, Josephine, may have been a factor in this decision—with the exception of A History of England (1911), in which he wrote the verse to punctuate C. R. L. Fletcher’s narrative.

If

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise:

If you can dream—and not make dreams your master;

If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools:

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

Much of the controversy that surrounds Rudyard Kipling stems from his conviction that it was the responsibility and right of the English to civilize the world’s heathen. The imperialistic phrase “the white man’s burden” was taken from Kipling’s poem of the same name (1899), in which he wrote, “Take up the White Man’s Burden— Send forth the best ye breed—Go bind your sons to exile—To serve your captives’ need.”

These paradoxes, Kipling’s jingoism, and his ability to understand the role of the outsider, as seen in Mowgli and Kim, leave biographers and critics puzzled. Nevertheless, the concerns of critics are not those of the children who read or listen to Kipling’s stories. That children today listen as eagerly to hear the adventures of Kim, the songs and wisdom of Baloo, and the hilarious myths of the animal kingdom as they did when these books were first published serves as a testimony to Rudyard Kipling’s power as a storyteller.

M.I.A.

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.