Share via:

William Steig – American author and illustrator, 1907-2003

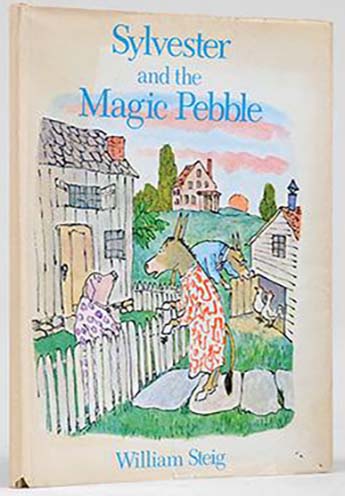

William Steig has been deservedly praised for both his writing and his illustrating, receiving the Caldecott Medal for Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (1969), a Caldecott honor for The Amazing Bone (1976), and two Newbery honors for Abel s Island (1976) and Doctor De Soto (1982).

William Steig grew up in the Bronx, where his father was a house painter and his mother a seamstress. He started painting at an early age. Among his influences, Steig credits the Grimms’ fairy tales, Charlie Chaplin’s movies, the Katzenjammer Kids, the opera Hansel and Gretel and Pinocchio. He has said, “If I’d had it my way, I’d have been a professional athlete, a sailor, a beachcomber, or some other form of hobo, a painter, a gardener, a novelist, a banjo-player, a traveler, anything but a rich man.”

During the Depression, when his father could not find work, it was up to young Steig to support his family, which he did quite successfully by selling cartoons to the New Yorker and other magazines. He has published several volumes of these drawings, which are often enigmatic, thought-provoking doodles. Steig attended City College in New York for two years, then spent four years at the National Academy of Design.

In the 1940s he began carving in wood, and his sculptures are in several museum collections. He came to children’s books late, when he was sixty, at the suggestion of Robert Kraus, a New Yorker colleague, and found immediate success. Since then he has written and illustrated more than twenty books and provided illustrations for eight more. He married his fourth wife in 1969 and has three children.

Describing his creative process, Steig has said, “I usually start a picture book by selecting a main character — donkey, mouse, or perhaps human. Then I decide what his or her occupation is and take it from there. I make a very rough dummy and afterward try to get the spontaneous quality of the rough drawings…. I like drawing, but not illustrating, because basically I’m a doodler. My best work is spontaneous and unconscious, as someone once pointed out, calling me a ‘sublime doodler’ — the best compliment I ever had.” Once an idea is accepted by his editor, Steig will work quickly, taking about a week to write the text and a month to illustrate.

William Steig’s illustrations are instantly recognizable, as he has used a consistent style involving a fairly thick, sketchy black line with watercolor added loosely, often including stripes, polka dots, and flowered patterns in his characters’ clothing and in the backgrounds. His prose has a forthright style, and he has used precise, often surprising language, which some adults fear is too challenging but which children love. He is serious about his characters and their situations.

This is real life, even if it involves a mouse dentist or a donkey with a magic pebble, and the humor comes from the believable situations and characteristics the reader recognizes from his or her own experiences. In even his most fantastical stories, the problems his characters face are universal and their solutions are never didactic. Steig has said, “I feel this way: I have a position — a point of view. But I don’t have to think about it to express it. I can write about anything and my point of view will come out. So when I am at work my conscious intention is to tell a story to the reader. All this other stuff takes place automatically.”

William Steig’s books provide serious situations factually illustrated with familiar settings and characters with intensely real emotions. His humor, alternately silly and poignant, and his integrity regarding his characters and his readers should ensure his popularity for many years.

William Steig in his own words …

I grew up in the Bronx. Lamplighters lit the old gas lamps; people sat on the stoops; gypsies wandered through the streets. Among the things that affected me most profoundly as a child were certain works of art: Grimms’ fairy tales, Charlie Chaplin movies, Humperdinck’s opera Hansel and Gretel, the Katzenjammer Kids, and Pinocchio. I can still remember the turmoil of emotions, the excitement, the fears, the delights, and the wonder with which I followed Pinocchio’s adventures.

I didn’t spend many years in school. I graduated from high school when I was fifteen and spent two years in the City College of New York where my biggest interest was not learning but playing — water polo. Then I went to the National Academy of Design. There was a time that I wanted to go to sea, and I had the necessary papers. If I’d had it my way, I’d have been a professional athlete, a sailor, a beachcomber, or some other form of hobo. When I was an adolescent, Tahiti was a paradise. I made up my mind to settle there someday. I was going to be a seaman, like Herman Melville, but the Great Depression put me to work.

My father didn’t want us to become laborers because we’d be exploited by businessmen, and he didn’t want us to become businessmen because then we’d exploit the laborers. Since he couldn’t afford to send us to school to become professionals, the arts were the only thing that remained. Now we were always poor. My father made six dollars a week and supported a family on that. Many years later came the Depression, and my father couldn’t find work — nor could my brothers. My father said, “It is up to you to do something.” So I started peddling cartoons. I flew out of the nest, with my family on my back.

I would have liked to become a writer. Since I had to make a living, I turned to cartooning. Cartooning is a kind of writing. I worked for a magazine called Life and a magazine called fudge. I Started selling my pieces in 1930. The New Yorker was founded in 1925, so I felt I had come five years late. I’m not the oldest contributor, but the lengthiest.

I got into children’s book writing by accident. Robert Kraus, who was a colleague at the New Yorker, started a company, Windmill, and asked me to write a children’s book. I actually even liked creating the color separations — the old method — because you have to imagine how the stuff is going to look. If you keep the color very simple, the results are usually good.

I like working on the longer books better because the process is more like writing. The Rea/ Thief is my favorite. I enjoyed writing Dominic, my first long book. I read my wife, Jeanne, a bit from the book every night, and she encouraged me to go on.

My books always evolve from a character. I decide who the chief character is, and once I have made him, say, a dentist, the story is on its way. J do as little drawing as possible in the beginning; I imagine the character. I draw when I create the dummy; then when I illustrate, I try to get the spontaneous quality of the drawing in the dummy.

My best drawing doesn’t appear anywhere, although it does occasionally in books. My biggest pleasure is just drawing. Sometimes I’m referred to as a doodler. I was flattered by someone’s comment that “Steig is a sublime doodler.” With illustration you have to repeat the same characters again and again, make sure they don’t change. My unconscious is more intelligent than my conscious. I often ask myself, “What would be an ideal life?” I think an ideal life would be just drawing.

The child is the hope of humanity. If they are going to change the world, they have to start off optimistically. I wouldn’t consider writing a depressing book for children.

This article is based on an Interview with William Steig conducted by Anita Silvey in September 1992.

L.R.

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.

William Steig Works

- 1932, Man About Town (New York: R. Long & R.R. Smith)

- 1939, About People: A book of symbolical drawings by William Steig (Random House)

- 1941, How to Become Extinct (Farrar & Rinehart), written by Will Cuppy, illustrated by Steig

- 1942, The Lonely Ones (Duell, Sloan and Pearce)

- 1944, All Embarrassed (Duell S&P)

- 1944, Small Fry (Duell S&P)

- 1945, Persistent Faces (Duell S&P)

- 1946, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (Simon & Schuster) by Eric Hodgins

- 1947, Till Death Do Us Part: Some ballet notes on marriage (Duell S&P)

- 1948, Listen, Little Man! (Orgone Institute Press) by Wilhelm Reich – translated from the German-language essay “Rede an den kleinen Mann”, 1945

- 1950, The Decline and Fall of Practically Everybody by Will Cuppy

- 1950, The Agony in the Kindergarten (Duell S&P)

- 1950, Giggle Box: Funny Stories for Boys and Girls (Alfred A. Knopf), compiled by Phyllis R. Fenner, newly illustrated by Steig

- 1951, The Rejected Lovers (Knopf)

- 1953, Dreams of Glory and other drawings (Knopf)

- 1963, Continuous Performance (Duell S&P)

From this time, Steig primarily created children’s picture books.

- 1968, CDB! (Windmill Books) – picture book

- 1968, Roland the Minstrel Pig (Windmill)

- 1969, Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (Windmill) — NBA finalist

- 1969, The Bad Island (Windmill)

- 1971, Amos and Boris

- 1972, Dominic — NBA finalist

- 1973, The Real Thief

- 1974, Farmer Palmer’s Wagon Ride

- 1976, Abel’s Island — adapted as a 1988 film

- 1976, The Amazing Bone

- 1977, Caleb + Kate — NBA finalist

- 1978, Tiffky Doofky 1979, Drawings

- 1980, Gorky Rises

- 1982, Doctor De Soto — National Book Award (NBA), Picture Books

- 1984, CDC? (Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

- 1984, Ruminations 1984, Yellow & Pink

- 1984, Rotten Island — his most popular book

- 1985, Solomon, The Rusty Nail 1986, Brave Irene

- 1987, The Zabajaba Jungle

- 1988, Spinky Sulks

- 1990, Shrek! — the basis for the movie series

- 1992, Alpha Beta Chowder, written by Jeanne Steig, illustrated by William Steig

- 1992, Doctor De Soto Goes to Africa

- 1994, Zeke Pippin

- 1996, The Toy Brother

- 1998, A Handful of Beans: Six Fairy Tales, retold by Jeanne Steig, illustrated by William Steig

- 1998, Pete’s a Pizza

- 2000, Made for Each Other

- 2000, Wizzil

- 2001, A Gift from Zeus

- 2002, Potch & Polly

- 2003, When Everybody Wore a Hat