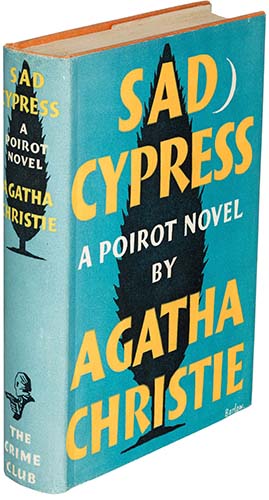

Sad Cypress is a work of detective fiction by British writer Agatha Christie, first published in the UK by the Collins Crime Club in March 1940 and in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company later in the same year. The UK edition retailed at eight shillings and threepence (8/3) – the first price rise for a UK Christie edition since her 1921 debut – and the US edition retailed at $2.00.

The novel was the first novel in the Poirot series set at least partly in the courtroom, with lawyers and witnesses exposing the facts underlying Poirot’s solution to the crimes. The story is written in three parts: in the first place an account, largely from the perspective of Elinor Carlisle of the death of her aunt, Laura Welman, and the subsequent death of Mary Gerrard; secondly Poirot’s account of his investigation in conversation with Dr Lord; and, thirdly, a sequence in court, again mainly from Elinor’s dazed perspective.

The title comes from a song from Act II, Scene IV of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night which is printed as an epigraph to the novel.

Come away, come away, death, And in sad cypress let me be laid; Fly away, fly away breath; I am slain by a fair cruel maid. My shroud of white, stuck all with yew, O, prepare it! My part of death, no one so true Did share it.

Plot Summary

[SPOILER ALERT]

Elinor Carlisle and Roddy Welman are engaged to be married when she receives an anonymous letter claiming that someone is “sucking up” to their wealthy aunt, Laura Welman, from whom Elinor and Roddy expect to inherit a sizeable fortune. Elinor is niece to Mrs Welman, while Roddy is nephew to her late husband. Elinor suspects Mary Gerrard as the topic of the anonymous letter, the lodgekeeper’s daughter, whom their aunt likes and supports. Neither guesses who wrote the letter, which is burned. They visit their aunt at Hunterbury. Roddy sees Mary Gerrard for the first time in a decade. Mrs Welman is partially paralyzed after a stroke and dislikes living that way. She tells both her physician Peter Lord and her niece how much she dislikes living without full health, wishing the doctor might end her pain, which he refuses to do. Roddy falls in love with Mary; this provokes Elinor to end their engagement. After a second stroke, Mrs Welman asks Elinor to make provision for Mary. Elinor assumes there is a will her aunt wants modified. Mrs Welman dies before Elinor can call the solicitor. There is no will. She dies intestate, so her considerable estate goes to Elinor outright as her only known surviving blood relative.

Elinor settles two thousand pounds on Mary, which Mary accepts. Elinor sells the house she inherited. Mary dies of morphine poisoning at an impromptu lunch at Hunterbury, as Elinor, at the house, and Mary with Nurse Hopkins, at the lodge, are clearing out private possessions. Everyone at the house had access to the morphine Nurse Hopkins claimed to have lost at Hunterbury while Mrs Welman was ill. Elinor is arrested. Later, after the body is exhumed, it is learned that her aunt died of morphine poisoning. Peter Lord, in love with Elinor, brings Poirot into the case. Poirot speaks to everyone in the village. He uncovers a second suspect when Roddy tells him of the anonymous letter – the writer of that letter. Poirot then focuses on a few elements. Was the poison in the sandwiches made by Elinor, which all three ate, or in the tea prepared by Nurse Hopkins and drunk by Mary and Hopkins, but not by Elinor? What is the secret of Mary’s birth? Is there any significance in the scratch of a rose thorn on Hopkins’s wrist? The denouement is revealed mainly in the court, as the defence lawyer brings witnesses who reveal what Poirot uncovers.

A torn pharmaceutical label that the prosecution says is from morphine hydrochloride, the poison, is rather a scrap from a label for apomorphine hydrochloride, an emetic, made clear because the m was lower case. The letters Apo had been torn off. Nurse Hopkins had injected herself with the emetic, to vomit the poison that she would ingest in the tea, explaining the mark on her wrist – not from a rose tree that is a thornless variety, Zephirine Drouhin. She went to wash dishes that fateful day for privacy as she vomited, looking pale when Elinor joined her in the kitchen. The motive was money. Mary Gerrard was the illegitimate daughter of Laura Welman and Sir Lewis Rycroft. Had this been discovered sooner, she would have inherited Mrs Welman’s estate. Nurse Hopkins knows Mary’s true parents because of a letter from her sister Eliza some years earlier. When Hopkins encouraged Mary Gerrard to write a will, Mary named as beneficiary the woman whom she supposes to be her aunt, Mary Riley, the sister of Eliza Gerrard, in New Zealand. Mary Riley’s married name is Mary Draper. Mary Draper of New Zealand it turns out is Nurse Hopkins in England, as two people from New Zealand who knew Mary Draper both confirm in court. Hopkins leaves the courtroom before the judge can recall her.

Elinor is acquitted, and Peter Lord takes her away from where reporters can find her. Poirot talks with Lord to explain his deductions and actions to him as he gathered information on the true murderer, and how the “quickness of air travel” allowed witnesses from New Zealand to be brought to the trial. Poirot tells Lord he understands his clumsy efforts to get some action in Poirot’s investigation. Lord’s embarrassment is alleviated by Poirot’s assurance that Lord will be Elinor’s husband, not Roddy.

Publication history

- 1940, Collins Crime Club (London), March, hardcover, 256 pp

- 1940, Dodd Mead & Co (New York), hardcover, 270 pp

- 1946, Dell Books, paperback, 224 pp (Dell number 172 mapback)

- 1959, Fontana Books (imprint of HarperCollins), paperback, 191 pp

The book was first serialised in the US in Collier’s Weekly in ten parts from 25 November 1939 (volume 104, number 22) to 27 January 1940 (volume 105, number 4) with illustrations by Mario Cooper.

The UK serialisation was in nineteen parts in the Daily Express from Saturday, 23 March to Saturday, 13 April 1940. The accompanying illustrations were uncredited. This version did not contain any chapter divisions.

Sad Cypress – First Edition Book Identification Guide

The books are listed in the order of publication. While the majority of Agatha Christie’s books were first published in the UK. There are many titles that were first published in the US. The title of the book may differs from the UK edition in some cases.

| Year | Title | Publisher | First edition/printing identification points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Sad Cypress | William Collins & Sons, London, [1940] | First edition. "Copyright 1940" stated on the copyright page. No statement of later printings. Orange cloth lettered in black. Price 8/3. |

| 1940 | Sad Cypress | Dodd, Mead & Co, NY, 1940 | First American edition. Date on the title & copyright page matches. No statement of later printings. Decorative blue cloth, lettered in black. Price $2.00. |

Note about Book Club Editions (BCE) and reprints:

UK: You can see statements of later reprint dates or of book club on the copyright page.

US: The US reprint publishers usually use the same sheets as the first edition and are harder to identify by looking at the title page or the copyright page. One may identify a BCE by looking at the DJ, which doesn’t have a price on top of the front flap and a “Book Club Edition” imprint at the bottom. If the dust jacked is clipped at both the top/bottom of the front flap. You can safely assume it’s a BCE . If the book is missing the dust jacket. Later BCE editions can be identified by its plain boards, while first printings are issued in quarter cloth.

Please refer to the gallery for detailed images of true first edition bindings and dust jackets.

Sad Cypress – First Edition Dust Jacket Identification Guide

First edition bindings and various dust jacket printings identification.