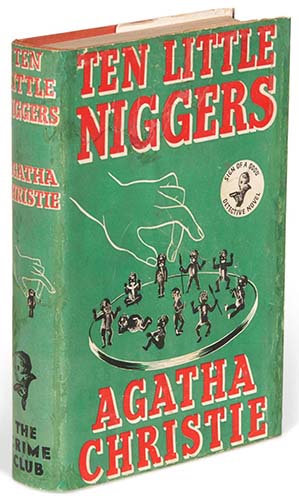

Ten Little Niggers is a mystery novel by the English writer Agatha Christie, described by her as the most difficult of her books to write. It was first published in the United Kingdom by the Collins Crime Club on 6 November 1939, after the children’s counting rhyme and minstrel song, which serves as a major plot element. The US edition was released in January 1940 with the title And Then There Were None, taken from the last five words of the song. Successive American reprints and adaptations use that title, though Pocket Books paperbacks used the title Ten Little Indians between 1964 and 1986. UK editions continued to use the original title until 1985.

And Then There Were None is the world’s best-selling mystery, and with over 100 million copies sold is one of the best-selling books of all time. The novel has been listed as the sixth best-selling title (any language, including reference works).

The plot is structured around the ten lines of the children’s counting rhyme “Ten Little Niggers” (“Ten Little Indians” or “Ten Little Soldiers” in later editions). Each of the ten victims – eight guests plus the island’s two caretakers – is killed in a manner which reflects one of the lines of the rhyme. Also killed, but off the island, is the island’s recent owner.

Plot Summary

[SPOILER ALERT]

These details correspond to the text of the 1939 first edition.

Eight people arrive on a small, isolated island off the Devon coast, each having received an unexpected personal invitation. They are met by the butler and cook-housekeeper, Thomas and Ethel Rogers, who explain that their hosts, Ulick Norman Owen and Una Nancy Owen, have not yet arrived, though they have left instructions.

A framed copy of an old rhyme hangs in every guest’s room, and on the dining room table sit ten figurines. After supper, a phonograph record is played; the recording accuses each visitor and Mr and Mrs Rogers of having committed murder, then asks if any of the “prisoners at the bar” wishes to offer a defence.

The guests discover that none of them know the Owens, and Mr Justice Wargrave suggests that the name “U N Owen” is a play on “Unknown”. Marston finishes his drink and promptly dies of cyanide poisoning. Dr Armstrong confirms that there was no cyanide in the other drinks and suggests that Marston must have dosed himself.

The next morning, Mrs Rogers is found dead in her bed, and by lunchtime, General MacArthur has also died from a heavy blow to the head. The guests realise that the nature of the deaths corresponds with the respective lines of the rhyme, and three of the figurines are found to be missing.

The guests suspect that U N Owen may be systematically murdering them and search the island, but find no hiding places. Since no one else could have arrived or departed the island unassisted, they are forced to conclude that one of the seven remaining persons must be the killer. The next morning, Mr Rogers is found dead at the woodpile, and Emily Brent is found dead in the drawing room, having been injected with potassium cyanide.

After Wargrave suggests searching all the rooms, Lombard’s gun is found to be missing. Vera Claythorne goes up to her room and screams when she finds seaweed hanging from the ceiling. Most of the remaining guests rush upstairs; when they return they find Wargrave still downstairs, crudely dressed in the attire of a judge with a gunshot wound to the forehead. Dr Armstrong pronounces him dead.

That night, Lombard’s gun is returned, and Blore sees someone leaving the house. Armstrong is absent from his room. Vera, Blore, and Lombard decide to stick together and leave the house. When Blore returns for food, he is killed by a marble clock shaped like a bear that is pushed from Vera’s window sill. Vera and Lombard find Armstrong’s body washed up on the beach, and each concludes the other must be responsible. Vera suggests moving the body from the shore as a mark of respect, but this is a pretext to acquire Lombard’s gun. When Lombard lunges for it, she shoots him dead.

Vera returns to the house in a shaken, post-traumatic state. She finds a noose and chair arranged in her room and a powerful smell of the sea. Overcome by guilt, she hangs herself in accordance with the last line of the rhyme.

Scotland Yard officials arrive on the island to find nobody alive. They discover that the island’s owner, a sleazy lawyer and drug trafficker called Isaac Morris, had arranged the invitations and ordered the recording. However, he had died of a barbiturate overdose on the night the guests arrived. The police reconstruct the deaths with the help of the victims’ diaries and a coroner’s report. They are able to eliminate several suspects due to the circumstances of their deaths and items being moved afterward, but ultimately they cannot identify the killer.

Much later, a trawler hauls up in its nets a bottle containing a written confession. In it, Mr Justice Wargrave recounts that all his life he had had two contradictory impulses: a strong sense of justice and a savage bloodlust. He had satisfied both through his profession as a criminal judge, sentencing murderers to death following their trial. After receiving a diagnosis of a terminal illness, he decided to put into effect a private scheme to deal with a group of people he considered to have escaped justice.

Before departing for the island, he had given Morris a lethal dose of barbiturates for his indigestion. He had faked his death by gunshot with the assistance of Dr Armstrong under the pretext that it would help the group identify the killer. After killing Armstrong and the other remaining guests and moving objects to confuse the police, he finally committed suicide by shooting himself in the head, using the gun and some elastic to ensure that his true death matched the account of his staged death recorded in the guests’ diaries. Wargrave had written his confession and thrown it into the sea in a bottle in response to what he acknowledged to be his “pitiful human need” for recognition.

Publication history

- 1939, Ten Little Niggers. London: Collins Crime Club., 256 pp. First edition.

- 1940, And Then There Were None. New York: Dodd, Mead., 264 pp. First US edition.

- 1944, And Then There Were None. New York: Pocket Books (Pocket number 261). Paperback, 173 pp.

- 1947, Ten Little Niggers. London: Pan Books (Pan number 4). Paperback, 190 pp.

- 1958, Ten Little Niggers. London: Penguin Books (Penguin number 1256). Paperback, 201 pp.

- 1963, Ten Little Niggers. London: Fontana. OCLC12503435. Paperback, 190 pp.

- 1964, Ten Little Indians. New York: Pocket Books. OCLC29462459. First publication of novel as Ten Little Indians.

- 1964, And Then There Were None. New York: Washington Square Press. Paperback, teacher’s edition.

The book was first serialised in the US in Collier’s Weekly in ten parts from 25 November 1939 (volume 104, number 22) to 27 January 1940 (volume 105, number 4) with illustrations by Mario Cooper.

The UK serialisation was in nineteen parts in the Daily Express from Saturday, 23 March to Saturday, 13 April 1940. The accompanying illustrations were uncredited. This version did not contain any chapter divisions.

Ten Little Niggers – First Edition Book Identification Guide

The books are listed in the order of publication. While the majority of Agatha Christie’s books were first published in the UK. There are many titles that were first published in the US. The title of the book may differs from the UK edition in some cases.

| Year | Title | Publisher | First edition/printing identification points |

|---|---|---|---|

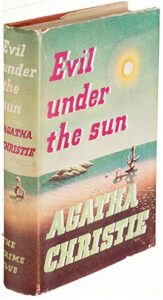

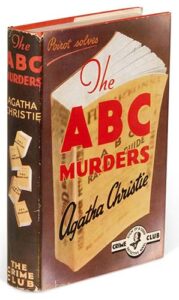

| 1939 | Ten Little Niggers | William Collins & Sons, London, [1939] | First edition. "Copyright 1939" stated on the copyright page. No statement of later printings. Orange or red cloth lettered in black. Price 7/6. |

| 1940 | And Then There Were None | Dodd, Mead & Co, NY, 1940 | First American edition. Date on the title & copyright page matches. No statement of later printings. Tan cloth lettered in red. Price $2.00. |

Note about Book Club Editions (BCE) and reprints:

UK: You can see statements of later reprint dates or of book club on the copyright page.

US: The US reprint publishers usually use the same sheets as the first edition and are harder to identify by looking at the title page or the copyright page. One may identify a BCE by looking at the DJ, which doesn’t have a price on top of the front flap and a “Book Club Edition” imprint at the bottom. If the dust jacked is clipped at both the top/bottom of the front flap. You can safely assume it’s a BCE . If the book is missing the dust jacket. Later BCE editions can be identified by its plain boards, while first printings are issued in quarter cloth.

Please refer to the gallery for detailed images of true first edition bindings and dust jackets.

Ten Little Niggers – First Edition Dust Jacket Identification Guide

First edition bindings and various dust jacket printings identification.