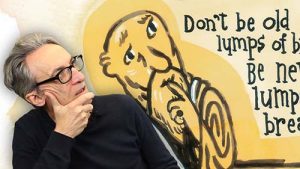

Edward Stratemeyer – American publisher, writer 1862-1930

Edward Stratemeyer (1862-1930) grew up in the era when Americans were taught that there was no accomplishment to which they could not aspire. The period in American history after the Civil War, especially in the victorious North, was one in which life was changing rapidly as Americans by the thousands left the countryside to move to the cities where opportunities were limitless. It was the age of Carnegie, Rockefeller, Morgan and many others who made it big in a big way. It was the era in which Horatio Alger wrote dozens of books proving how “living right paid off.” At least it seemed this way, and Stratemeyer must have believed it was. He did not become successful with iron and steel, oil or finance; he did become the most prolific American writer and/or book producer of ail time. Yet he was never blamed for creating a monopoly, as were the “robber barons” of the era.

Edward Stratemeyer, who had only an eighth-grade education, was a voracious reader of the juvenile literature of his time. Imitating the popular works he preferred, he wrote I and published his first story in the boys’ magazine Golden Days in 1889, for which he received $75, a goodly amount of money then. He was later hired by Street and Smith, publishers of dime novels and fiction magazines, where he met his childhood’s idols, Oliver Optic and Horatio Alger, Jr., the authors of the “living right pays off” a juvenile novels he read as a youth. At Street and Smith, Stratemeyer edited and finished the books Alger and Optic had not completed at the time of their deaths and he also wrote at least eleven new volumes under the Alger name.

From 1894 to 1908, Edward Stratemeyer wrote about seventy-five boys’ books in several different series and these were published under his own name by various companies that concentrated on the juvenile market, such as Lothrop, Lee & Shephard. These books were about boys and their adventures, success stories of the Alger type and patriotic volumes dealing with American bravery in the Revolution and other wars. The most successful of these books was Under Dewey at Manila, published in 1898 at the time of the American victory over Spain in a brief and popular war.

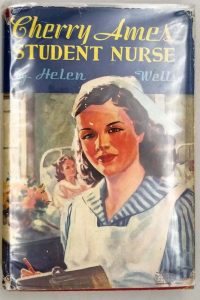

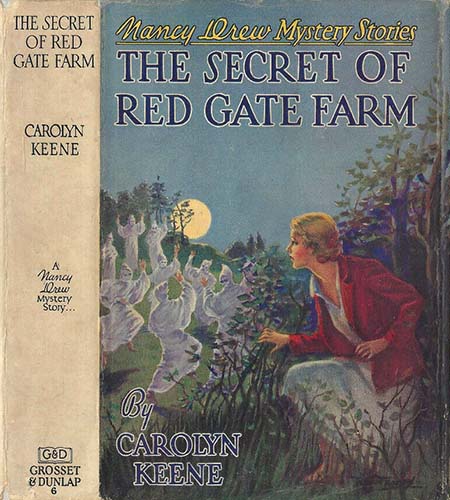

Around 1906, Edward Stratemeyer formed a syndicate to complete all the book ideas he was developing. It is estimated that he personally wrote about 200 books and that he outlined and edited another few hundred that were finished by ghostwriters. The most popular of these were Tom Swiff, the Rover Boys, the Bobbsey Twins, Baseball Joe, the Outdoor Girls, Ruth Fielding, Honey Bunch, Bomba the Jungle Boy, Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys. Stratemeyer created many pen names for the “authors” of these series books. Many of the names had obvious meanings, such as Arthur M. Winfield, the “author” of the Rover Boys books. Arthur is a homonym for author, “M” is for the millions (of books or dollars) hoped for and “Winfield” stood for success.

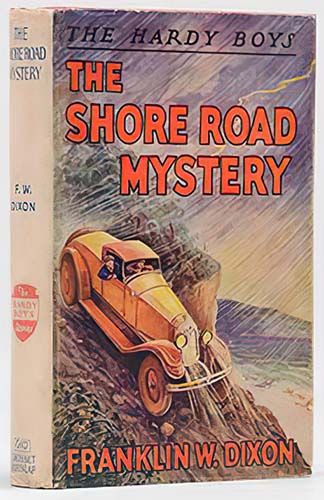

No one person could produce all the books Edward Stratemeyer had in mind so he hired writers who finished books that he plotted and outlined and they were published under “house names.” A good example of this is Laura Lee Hope, author of the Bobbsey Twins books, the longest running Stratemeyer series, which was published from 1904 until about 1990. Many different writers worked on this list and on “Miss Hope’s” other works, such as the Six Little Bunkers, the Outdoor Girls and the Moving Picture Girls. Ghostwriters who filled in the details of the stories were paid a flat rate of about $75 to $100 (some writers probably commanded more) for each completed 200-page book. Lately there has been a great number of articles and books decrying the practice of paying the ghostwriters so little.

How long would it require to write a Bobbsey Twins book in 1925? Two weeks? A month? At any rate, the number of words in the book was less than the average newspaper reporter wrote in a week for a salary of about $20 per week. A certain amount of talent and imagination was required to fill in the details of a Stratemeyer Syndicate book, but the real credit does seem to belong to Edward Stratemeyer and his successors who provided most of the creativity. Some of the most important Stratemeyer writers were the ones who worked on the three most enduring series. These are Howard R. Garis who wrote about twenty-five Bobbsey Twins books and thirty-five Tom Swift ones; Mildred A. Wirt who created several of the Ruth Fielding, Nancy Drew, and Kay Tracey books; and Leslie McFarlane who did the Hardy Boys books for the first twenty years. The identities of these authors were kept secret (by contract) for most of the 20th century.

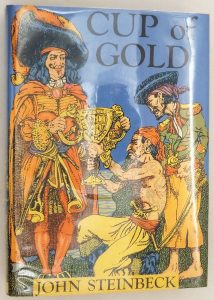

Another Stratemeyer invention was the 50-cent book. In 1906, a Five Little Peppers book from Lothrop, Lee & Shephard cost $1.50; other publishers’ juvenile series were priced about the same. Cuppies & Leon’s and Grosset & Dunlap’s 50-cent Stratemeyer books had heavy cloth-covered covers, a full color dust jacket, from one to four internal illustrations, heavy acid-free paper, and clear typesetting with large print. Librarians considered none of these books “literature” and they were not found in public libraries until very recently. This factor probably caused more books to be sold than anything else, as young people loved them and wanted to read them. The volume of old copies still available for collectors proves that many millions were printed. All of the Stratemeyer Syndicate books showed several generations of juveniles a positive, affirmative, and enthusiastic view of American life. They always gave hope for a promising future and, like Alger’s books, proved that “living right pays.” It is true that there were racial and ethnic stereotypes in the books, but there were probably less than in adult fiction of the same period.

The Stratemeyer Syndicate supplied the publishing houses that catered to the juvenile market, such as Cuppies & Leon and Grosset & Dunlap, with product during the entire 20th century. Mr. Stratemeyer was always astute in designing new series books and addressed the popular adult trends by creating a similar juvenile market. Examples of this are Bomba the Jungle Boy, an obvious Tarzan-type; all the Moving Picture series of the period in which the movies were developing as popular entertainment; and the teenage detectives like Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys who were introduced at the time of rising popularity in adult detective fiction.

When Stratemeyer died in 1930, his daughters, Harriet Stratemeyer Adams and Edna Stratemeyer Squier, continued with his work and the Stratemeyer Syndicate, consolidating the policies begun by their father.

– John Axe

Source: All About Collecting Boys’ Series Books. John Axe, 2002.