Paul O. Zelinsky – American illustrator, b. 1953.

Paul O. Zelinsky was born in Evanston, Illinois. His father, a college professor, taught in various places, so the family moved often; Zelinsky, forced to make new friends, found that his predilection for drawing made him the “class artist” wherever he lived. When he was in high school, he learned printmaking and made etchings and linoleum cuts to illustrate stories and poems that others wrote.

In college, he was introduced to children’s books in a class taught by author illustrator Maurice Sendak on the history and making of children’s books. He graduated from Yale University in 1974 and received an M.EA. degree in painting from Tyler School of Art in 1976.

Paul O. Zelinsky’s first picture book was Boris Zhitkov’s How I Hunted the Little Fellows (1979), a Russian story that allowed him to research late-nineteenth-century Russian interiors. He then illustrated a novel by Avi, The History of Helpless Harry: To Which Is Added a Variety of Amusing and Entertaining Adventures (1960), which was set in 1845.

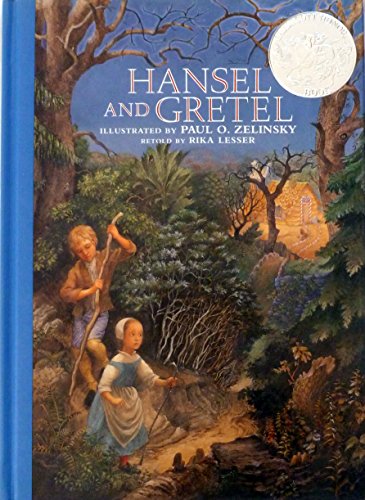

He was pulled ahead to the current century with Ralph S. Mouse (1982), his first assignment to illustrate a novel by Beverly Cleary, Cleary’s Newbery Medal winning Dear Mr. Henshaw came next, in 1983. These books brought Paul Zelinsky’s work to the attention of the widest possible audience in the field of books for children, so that when his magnificent Hansel and Gretel appeared in 1984, many adults in the children’s book field knew his name.

Rich paintings with details redolent of a more romantic and a more rustic time limn the familiar tale of two children who best a witch. The book was named a Caldecott Honor Book by the American Library Association, as was his Rumpelstiltskin (1986). The latter was exhibited in an American Institute of Graphic Artists show, as were several others of his books, and was also named a Bratislava Biennale selection by the International Board on Books for Young People. Paul Zelinsky won the Caldecott Medal for his lush illustrations for a Grimm story, Rapunzel (1997).

A completely different picture book style is used in The Maid and the Mouse and the Odd- Shaped House (1981), which is based on a late- nineteenth-century “tell-and-draw” story designed to be created on a school blackboard, with each child adding to the picture. Zelinsky’s mastery of book design is evident in this deceptively simple, whimsical, and clever book. The book was chosen by judges to appear in the Horn Book Magazine “Graphic Gallery” as an example of admirable illustration and design criteria, and it was a New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Book of 1981.

Another picture book, The Story of Mrs. Lovewright and Purrless Her Cat (1985), is a story by Lore Segal, illustrated to full comic effect. It too was named a New York Times Best Illustrated Childrens Book. In one of his most brilliant books, Anne Isaacs Swamp Angel (1994), which received a Caldecott Honor award, Zelinsky re-created American folk art and primitive American painting to illustrate the tall tale of a great woodswoman of Tennessee.

Paul O. Zelinsky is capable of humor and an almost cartoonish style as in Mrs. Lovewright and of geometrically drawn, clean lines and innovative design as in The Maid and the Mouse. He can paint sumptuous pictures for traditional tales, such as the forest scenes and the gingerbread house in Hansel and Gretel, with lush detail and intricate composition. Clearly, this artist is capable of completely changing his approach to design and his style of illustration with practically every book and with repeated success.

Paul O. Zelinsky in his own words …

I fell short in my art school training because I never quite believed in Quality of Edge or Color Relationship as a painting’s only reason for being; I was, and still am, happier trying to put these abstract qualities in the service of something else, such as a story.

Every story is a different experience, carries its own feelings and associations. When I read a story to illustrate it, I want to capture the feelings — grab them and hold on, because they can be fleeting — and figure out how to make pictures that support and intensify them. This problem demands abstract solutions (a quality of line, a kind of space, a color relationship), which often means playing with new and different media: pencil, pastel, oils, on paper, canvas, drafting film, wood. But increasingly, I spend time Just thinking about the feelings in the story.

Often these feelings come to me as a sort of flavor I know that when I call up my earliest memories, what I remember seeing and hearing is accompanied by a flavorlike sense of what it felt like to be there and see that It is usually a wonderful sense, belonging to the whole experience, the way the smell of a room can become the whole experience of the room. Some years ago I was reading my daughter a Babar book for the second or third time when suddenly an illustration (of the monkeys’ tree houses) sparked a lost memory.

It was simply the memory of that same page, but as I had seen it as a young child. Not only did the crudeness of the drawing fall away in this child’s- eye view, and the sketchy detail blossom into something incredible, but the whole scene was enveloped in a kind of air, had a particular quality. Suddenly I could breathe, smell, and taste this world. So, too, with each new text I take on, I want to grasp what its taste is, and bring it out in the pictures.

When I first learned the song “The Wheels on the Bus” I knew I wanted to illustrate it someday (I was well out of kindergarten and already illustrating books). My literal mind immediately suggested a book where the bus’s moving parts would really move. But what should the pictures look like? The song reminded me a little of bubble gum: it was sweet and bouncy. The pictures needed plenty of rhythm, and the sense of sinking your teeth into something. I thought thick oil paint might give that chewy feeling. And the palette of colors I eventually came up with does, I think, give some of the same kind of pleasure as sweets do. There was also a physical pleasure in the laying down of paint and the way colored pencil lines would sometimes plow through the wet oils. Altogether the flavor is strong and full of energy. I hope the pictures are more nutritious, though, than bubble gum.

Lore Segal’s marvelous ear for language gave The Story of Mrs. Lovewright and Purrless Her Cat a tangy qualify. I think perhaps of dill pickles, which are sour, deliciously flavorful, and somehow unintentionally funny. Looking for ways to make these feelings visual, I saw all stretched-out shapes and sharp angles. (Not how a pickle looks, certainly, but how I think the taste of a pickle would look.) Mrs. Lovewright was so uncomfortable a person — a chilly woman, trying vainly to make things cozy by cuddling with an unwilling cat. The drawings were in colored pencil; its line has a fittingly edgy qualify, unlike, say, watercolor.

I used watercolor as well as opaque watercolor and pastels for Mirra Ginsburg’s good-night book, The Sun’s Asleep Behind the Hill. This chantlike text seems to breathe the smells of a summer night. Soft and darkening by degrees, the watercolor pictures took on a filmy haze of color, consisting of pastels rubbed onto the thumb and smeared over the paper. The best pictures were done while house-sitting for friends in the country, where night came on slowly and I was alone to sense the changes of color and the sounds and smells in the air

That was an attempt to bring some real-life experience into the illumination of a text. Drawing Rumpelstiltskin was an effort to create a purely imagined world. It called for a sort of perfect beauty: smooth surfaces placed in a clear light, reminiscent of the paintings of the Northern Renaissance. These were painted in many transparent layers of carefully applied oil paint, and I worked out my own version of the technique. I would have liked to paint what it’s like on the inside of a jewel — bright and still, perhaps with no smell at all.

It seems I give myself the task with every book of inventing a new way of working toward a different effect. Three-quarters of the way through each project, I wonder why it has taken so very long before the drawing started to flow. It is hard to remember after the fact how much trial and error — and error and error — go into the earliest stage of the work of illustrating: sensing the flavor of a text, and figuring out how to capture it for the eyes.

S.H.H.

Source: Children’s Books and their Creators, Anita Silvey.

Paul O. Zelinsky Books

As writer and illustrator

- The Maid and the Mouse and the Odd-Shaped House: A Story in Rhyme (1981) – adapted from a school exercise

- The Lion and the Stoat (Greenwillow Books, 1984) – based in part on natural history by Pliny the Elder

- Rumpelstiltskin, retold (1986) – Brothers Grimm

- The Wheels on the Bus, paper engineer Rodger Smith (Dutton, 1990) – adapted from the children’s folk song; “A Book with Parts that Move”

- Rapunzel, retold (1997) – from the Brothers Grimm (1812)

- Knick-Knack Paddywhack!, paper engineer Andrew Baron (Dutton, 2002) – adapted from the nursery rhyme “This Old Man”; “A Moving Parts Book Adapted from the Counting Song”

As illustrator

- Emily Upham’s Revenge, or How Deadwood Dick Saved the Banker’s Niece: A Massachusetts Adventure, written by Avi (Pantheon Books, 1978)

- How I Hunted the Little Fellows, Boris Zhitkov, transl. from Russian by Djemma Bider (Dodd, Mead, 1979)

- The History of Helpless Harry, to Which is Added a Variety of Amusing and Entertaining Adventures, Avi (1980)

- What Amanda Saw, Naomi Lazard (1981)

- Three Romances: Love Stories from Camelot Retold, Winifred Rosen (1981)

- Ralph S. Mouse, Beverly Cleary (1982)

- The Sun’s Asleep Behind the Hill, Mirra Ginsburg (1982) – adapted from an Armenian song

- The Song in the Walnut Grove, David Kherdian (1982)

- Dear Mr. Henshaw, Beverly Cleary (1983)

- Zoo Doings: Animal Poems, Jack Prelutsky (1983)

- Hansel and Gretel, retold by Rika Lesser (1984)

- The Story of Mrs. Lovewright and Her Purrless Cat, Lore Segal (1985)

- The Random House Book of Humor for Children, selected by Pamela Pollack (1988)

- The Big Book for Peace, Myra Cohn Livingston (1990)

- Strider, Beverly Cleary (1991)

- The Enchanted Castle, E. Nesbit (1992; orig. 1907)

- More Rootabagas, posthumous collection by Carl Sandburg, ed. George Hendrick (1993)

- Swamp Angel, Anne Isaacs (Dutton Children’s Books, 1994)

- Five Children and It, E. Nesbit (1999; orig. 1902)

- Awful Ogre’s Awful Day, Jack Prelutsky (2000) – poems

- Doodler Doodling, Rita Golden Gelman (2004)

- Toys Go Out series, children’s novels by Emily Jenkins, published by Schwartz & Wade

- Toys Go Out: Being the Adventures of a Knowledgeable Stingray, a Toughy Little Buffalo, and Someone called Plastic (2006)

- Toy Dance Party: Being the Further Adventures of a Bossyboots Stingray, a Courageous Buffalo, and a Hopeful Round Someone called Plastic (2008)

- Toys Come Home: Being the Early Experiences of an Intelligent Stingray, a Brave Buffalo, and a Brand-New Someone called Plastic (2011)

- Toys Meet Snow: Being the Wintertime Adventures of a Curious Stuffed Buffalo, a Sensitive Plush Stingray, and a Book-Loving Rubber Ball (forthcoming 2015)

- The Shivers in the Fridge, Fran Manushkin (2006)

- Awful Ogre Running Wild, Jack Prelutsky (2008) – poems

- Dust Devil, Anne Isaacs (Random House/Schwartz & Wade, 2010) – sequel to Swamp Angel

- Z is for Moose, Kelly Bingham (2012)

- Earwig and the Witch, Diana Wynne Jones (2012)

- Circle, Square, Moose, Kelly Bingham (2014) – sequel to Z is for Moose