Share via:

J.R.R. Tolkien – British scholar and writer, 1892-1973.

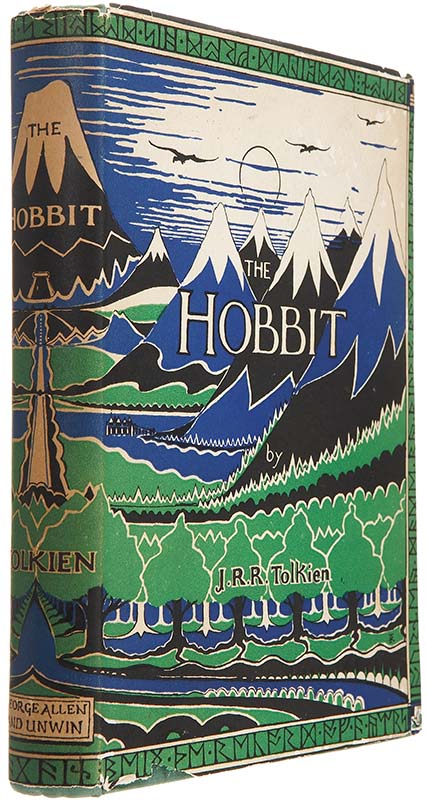

British scholar and writer, 1892-1973. John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s The Hobbit or, There and Back Again (1937), with illustrations by the author, is a captivating fantasy with wide appeal for both children and adults. It concerns the quest of Bilbo Baggins, a comfort-loving, ordinary, and unambitious hero. The New York Herald Tribune awarded it a prize as the best book published for young children in the spring of 1938.

That year, J.R.R. Tolkien’s friend and colleague, C.S. Lewis, wrote, “The Hobbit may well prove a classic.” The Hobbit, in fact, has proved to be the most popular of all twentieth-century fantasies written for children. Tolkien was so well grounded in ancient legend and saga, medieval literature, his own original languages, and philological study of the connections between language and literature, that there was, as Lewis said, “a happy fusion of the scholar’s with the poet’s grasp of mythology.”

According to Tolkien, his stories “arose in the mind as ‘given’ things, and as they came, separately, so too the links grew. . . always I had the sense of recording what was already ‘there,’ somewhere, not of ‘inventing'” time when fairy stories were considered childish, Tolkien claimed in a 1939 lecture, “On Fairy-Stories,” collected in Tree and Leaf (1964), that

“If fairy-story as a kind is worth reading at all it is worthy to be written for and read by adults.”

For Tolkien, children were not a race or class apart from adults, but fellow humans of fewer experiences, and thus, usually, had less need for the fantasy, recovery, escape, and consolation provided by fairy stories. He had enjoyed fairy stories during his own childhood, but it was not until “the threshold of manhood,” when his philological studies had made clear to him the connections between the origins of stories, language, and the creative human mind, that he developed a real taste for them.

Fantasy, he said, is a natural human activity and is not in opposition to ream. We make or create from our imagination “because we are made; and not only made, but made in the troy and likeness of a Maker.” The storymaker is a successful subcreator when his secondary world can be entered by the reader who is convinced by the inner consistency of the laws of that world that his experiences are “true.” Later twentieth-century writers of fantasy for children, such as Lloyd Alexander, Susan Cooper, Rosin McKinley, and others, reflect some Tolkien influence.

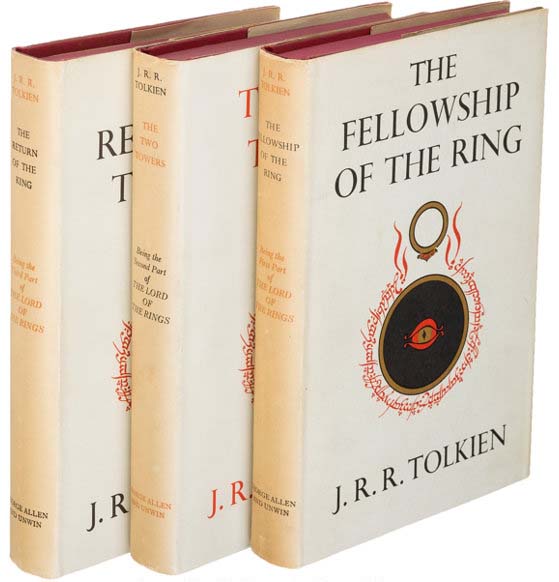

As reprintings of The Hobbit continued, there followed many requests for more about hobbits. But it was not until seventeen years later that the long-awaited “sequel” finally appeared. It was The Lord of the Ring (1954-55), published in three volumes: Part I, “The Fellowship of the Ring”; Part II, “The Two Towers” and Part III, “The Return of the King.”

Some of the delay was caused by the author’s need to ensure that the geography, chronology, and nomenclature were perfectly consistent within the sequel; with its predecessor, The Hobbit (which required a revised edition, published in 1951); and with the foundation “history,” a large body of unpublished original legends and many-layered mythologies of Elven lore of the “First Age of the World.”

Since early adulthood, Tolkien had been engaged in the process of inventing variants, revising, and finely tuning integrations of this material, and he continued to do so until his death, (Much of this “history” was published posthumously as The Silmarillion [1977] and additional volumes have appeared since the early edited by Christopher Tolkien, who had worked close With his father.)

When the first part of The Rings appeared, C. S. Lewis again gave Tolkien’s work generous praise:

“This book is like lightning from a clear sky. To say that in it heroic romance, gorgeous, eloquent and unashamed, has suddenly returned at period almost pathological in its anti-romanticism is inadequate … it makes … an advance or revolution: the conquest of new territory.”

In a short six weeks the first edition had sold out, demonstrating its popularity for a wide age range. Several years later, when a pirated paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings (and later an authorized one) became available, both works soared to die best-seller lists.

The sequels, similarly structured, share the time frame of “The Third Age of Middle Earth” and both are purported to have roots in the events of “The First Age”; but they differ in complexity and tone. The narrative tone is more relaxed and humorous in Bilbo’s story, where there are occasional asides to children, and there are only a few fleeting glimpses of “ the older matter.” In The Lord of the Rings, however, Tolkien claimed that he was “discovering” the significance of these “glimpses” and expanding on their relation to his “Ancient histories.”

The primary link between the sequels is the Ring of Power, treacherously forged by Sauron to control Elven-kings, Dwarf-lords, and Mortal Men. Central to a deeper understanding of Tolkien’s life mind are two short allegories, Leaf by Niggle (1947) and Smith of Wooton Major T967. Both can be enjoyed by children, but in each case the stones have deeper meaning for adults. The first represents the author’s fear of dying before he had completed the Lord of the Rings. and in the second the author recognizes that the gift that permits his visits to the land of faery must be relinquished and passed on to another generation.

A humorous dragon story with more child appeal is Farmer Giles of Ham (1949). The Adventures of Tom Bombadil (1962) contains entertaining verses from “The Red Book,” also the alleged source of The Hobbit. This collection, as well as Bilbo’s Last Song (1974), is illustrated by Pauline Baynes, whose work greatly pleased Tolkien. The Father Christmas Letters (1976) and Mr. Bliss (1982) are both illustrated by the author and are evidence of his special joy in creating stories for his children.

The enormous popularity of Tolkien’s work on American campuses during the 1960s may have slowed the Academy’s appreciation of his fiction. His academic reputation was well established. He had occupied two chairs as Professor of Anglo-Saxon and Professor of English Language and Literature, had lectured far more than was required, and had produced valued research publications.

An authorized biography by Humphrey Carpenter (1977) and the appearance of J.R.R. Tolkien’s letters (1981) stimulated academic attention. By the 1990s, his works had found their place in the canon of English literature and are now the subject of hundreds of critical and scholarly books, essays, dissertations, theses, and journal articles.

He received many honors in the last two decades of his life, including honorary doctorates from University College, Dublin, and from Liege in 1954, and for his work in philology from Oxford University, in 1972. The same year he was awarded the Order of the British Empire. J.R.R. Tolkien’s books have been translated into more than twenty-six languages and have reached annual worldwide sales of several million copies.

§ Elizabeth C. Hoke

Source: Children’s Book and their Creators, Anita Silvey.

J.R.R. Tolkien Collector’s Guide

J. R. R. Tolkien – First Editions Identification Guide.

J.R.R. Tolkien Books

- A Middle English Vocabulary. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1922. (This is presently bound in with Fourteenth Century Verse & Prose, ed. Kenneth Sisam, from Oxford University Press.) A glossary of Middle English words for students.

- Sir Gawain & The Green Knight. Ed. J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1925. (Now available in a second edition edited by Norman Davis.) A modern translation of the Middle English romance from the stories of King Arthur.

- The Hobbit: or There and Back Again. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1937. (There was a second edition in 1951, and a third in 1966. Reprinted many times.) The bedtime story for his children famously begun on the blank page of an exam script that tells the tale of Bilbo Baggins and the dwarves in their quest to take back the Lonely Mountain from Smaug the dragon.

- Farmer Giles of Ham. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1949. A faux-medieval tale of a farmer and his adventures with giants, dragons, and the machinations of courtly life.

- The Fellowship of the Ring: being the first part of The Lord of the Rings. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1954. second edition, 1966. One of the world’s most famous books that continues the tale of the ring Bilbo found in The Hobbit and what comes next for it, him, and his nephew Frodo.

- The Two Towers: being the second part of The Lord of the Rings. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1954. Second edition, 1966. The continuation of the story begun in The Fellowship of the Ring as Frodo and his companions continue their various journeys.

- The Return of the King: being the third part of The Lord of the Rings. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1955. Second edition, 1966. The conclusion to the story that we began in The Fellowship of the Ring and the perils faced by Frodo et al.

- The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1962. A collection of sixteen ‘hobbit’ verses and poems taken from ‘The Red Book of Westmarch’.

- Ancrene Wisse: The English Text of the Ancrene Riwle. Early English Text Society, Original Series No. 249. Oxford University Press, London, 1962. An edition of the Rule for a female medieval religious order.

- Tree and Leaf. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1964. New edition, incorporating “Mythopoeia”, Unwin Hyman, London, 1988. Reprints Tolkien’s lecture “On Fairy-Stories” and his short story “Leaf by Niggle”.

- Smith of Wootton Major. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1967. A short story of a small English village and its customs, its Smith, and his journeys into Faery.

- The Road Goes Ever On: A Song Cycle. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1967; George Allen and Unwin, London, 1968. (Second edition in 1978.) A collection of eight songs, 7 from The Lord of the Rings, set to music by Donald Swann.

- Bilbo’s Last Song. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1974. Originally produced as a poster image illustrated by Pauline Baynes, reprinted several times. First published as a hardback with new illustrations by Pauline Baynes by Unwin Hyman in 1990.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl and Sir Orfeo. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1975. Tolkien’s translations of these Middle English poems collected together.

- The Father Christmas Letters. Ed. Baillie Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1976. A collection of Tolkien’s own illustrated letters from Father Christmas to his children.

- The Silmarillion. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1977. Tolkien’s own mythological tales, collected together by his son and literary executor, of the beginnings of Middle-earth (and the tales of the High Elves and the First Ages) which he worked on and rewrote over more than 50 years.